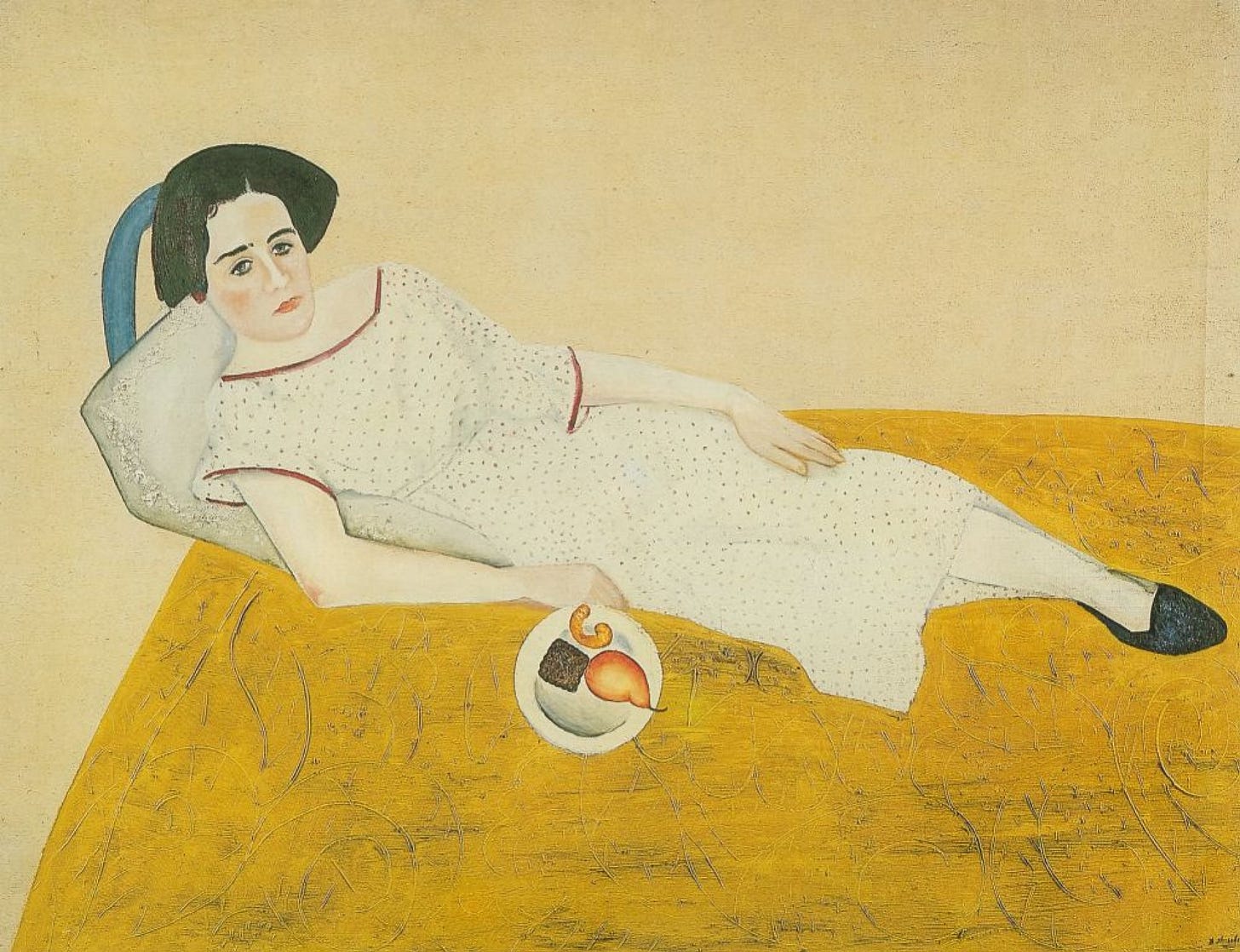

Gold is the colour of these waning days, as we navigate the border between summer and fall.

From Helen Hunt Jackson’s poem September: O golden month! How high thy gold is heaped!

Shadows dance languidly across wooden floors in early evening. In fields, stalks stand tall awaiting harvest. As always, I want to hold on to the season (the cicadas, heat, roses) but autumn has arrived; the oak leaves are beginning to rust. I’m reminded of this poem by Mary Chivers, titled Late August:

I ache for what I cannot keep - the birds,

the phlox, the late-flying bees -

though I would not forbid the frost,

even if I could. There will be more to love

and lose in what's to come and this too: desire

to see it clear before it's gone.

August was moonlight on the ocean, summer storms that felt like they would take the roof with them, islands both real and fictional, infinite cups of coffee, bookstores, watching clouds drift over the Rockies and prairies from airplane windows, a maddening spell of poison ivy, sentences sought, pages savoured.

Part of August was spent in a cabin with no electricity, a setting that inspired the novel I’ve been working on, a landscape steeped in lore. Islands are inherently mysterious—what type of people do they attract? What makes them want to stay? In my novel, a young woman is drawn to an island with an arcane past. She expects to hide out there, bide time; she is being monitored, followed. The island presents a fallacy of escape, as if all you can do here is leave / and plunge, never to return, into the depths.1 An island has a way about it, embedding itself in its visitor. It is like a room with no corners.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Girls on the Page to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.