Rachel Schwartzmann’s Slowing: Discover Wonder, Beauty, and Creativity through Slow Living, published September 17th by Chronicle Books, serves as a gentle nudge in a promising direction. It’s a roadmap of possibility, a web of inspiration, a portal. Read it and feel lighter. Read it and feel enlightened.

Audiences will recognize Rachel Schwartzmann as host of the podcast Slow Stories, where she interviews creatives like Chelsea Hodson, Tembe Denton-Hurst, and Ross Gay, and from thoughtful dispatches on Instagram where her posts celebrate the wonder of the day-to-day. Whether recommending a new novel, highlighting her sartorial sensibilities and the rhythms of each season, or offering the simple miracle of a rainbow reflected on a living room wall, Schwartzmann is a keen observer of the world around her—an awareness that radiates within the pages of Slowing.

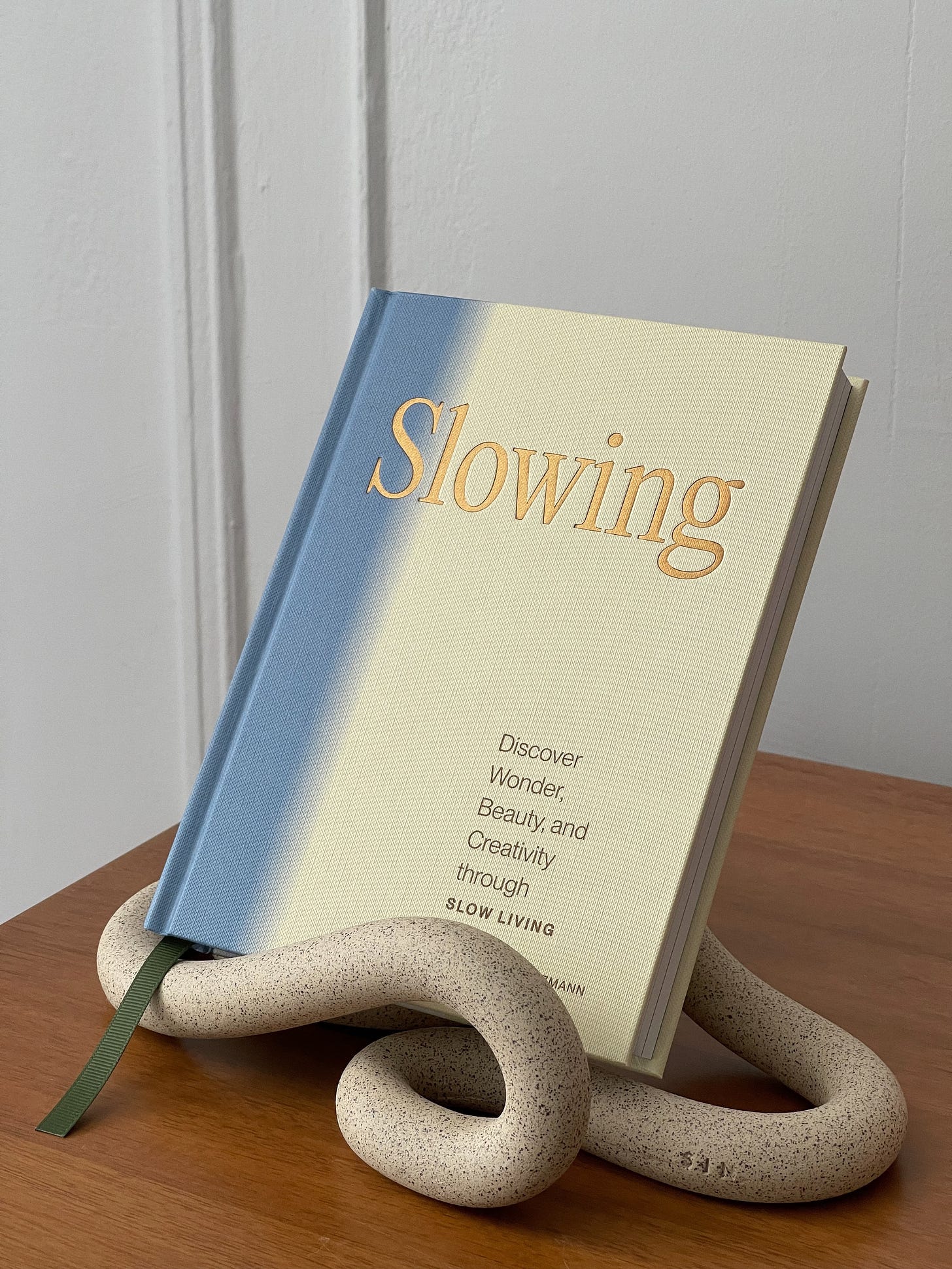

Slightly smaller than a textbook and possessing a cover which channels "the palette of the sky”, Slowing is a ruminative guide to living and creating with intention. Featuring a collection of personal essays, exercises (Create something for your eyes only, one of the prompts encourages. What is it like to make something that won’t be consumed by anyone else?), and interviews with creatives, Slowing is a book to read in leisurely increments and then share—with a parent, a sibling, a friend, a stranger.

Establishing Schwartzmann as an exceptional literary voice, Slowing weaves a stunning tapestry which honors the beauty that surfaces when the mundane is made magical—“Though this isn’t a self-help book, please help yourself to these sentences. Take these lessons with you to work. Rest your fingers on the spine. Tuck these secrets into bed with you. Let these slow stories humble you to the core, and—when you feel your feet beneath the ground again—finally exhale.”

Congratulations on the release of Slowing! How does it feel to have it out in the world?

Thank you so much! I’m writing to you in late October, and it still really hasn’t hit me in some ways… but then I’ll pop into my local bookstore and sign a copy and think, Oh, that’s mine.

So, if I had to sum it up, I feel incredibly grateful. People have shared their favorite passages and how Slowing has helped them through difficult times. I’ve received these messages from all over the world: Australia, Belgium, Brazil, Mexico, New Zealand—the list goes on. As a reader myself, it’s a gift to have such generous readers of my own.

In a recent interview with ELLE you mention that Slowing was initially supposed to be a collection of interviews—the essays came later. I’d love to hear more about what the process of dreaming up and mapping out the book was like. How did you decide upon including the timestamps and essays?

In truth, I had always wanted to include more of my voice in Slowing but didn’t know if I felt ready to step into my identity as a writer. I mention this in both the book and, more recently, in an essay I published in Literary Hub, but writing, in many ways, is my slowest story. Professionally, I had a winding path to Slowing—I feel that I really became a writer in tandem with getting this project off the ground, which made for an immersive experience.

I’m grateful to those who recognized my potential—a lot of editorial feedback I got while the book was on submission was to include more of my voice. My editor at Chronicle Books particularly encouraged that. As the process unfolded, we both didn’t realize just how personal Slowing would lean but ultimately felt it would resonate more (especially when exploring themes like slowing down, which can sometimes venture into prescriptive territory).

The structure was always the same, though: In the vein of slow storytelling and time, I wanted to unpack what beginnings, middles, and endings looked and felt like—and potentially reimagine what those chapters could be. (Every day, story, life has them!) Whether the explorations were coming from me or my interviewees, those three anchors felt like the right way to organize the stories. (The correlating prompts in each section were a way for readers to reflect on these themes as well.)

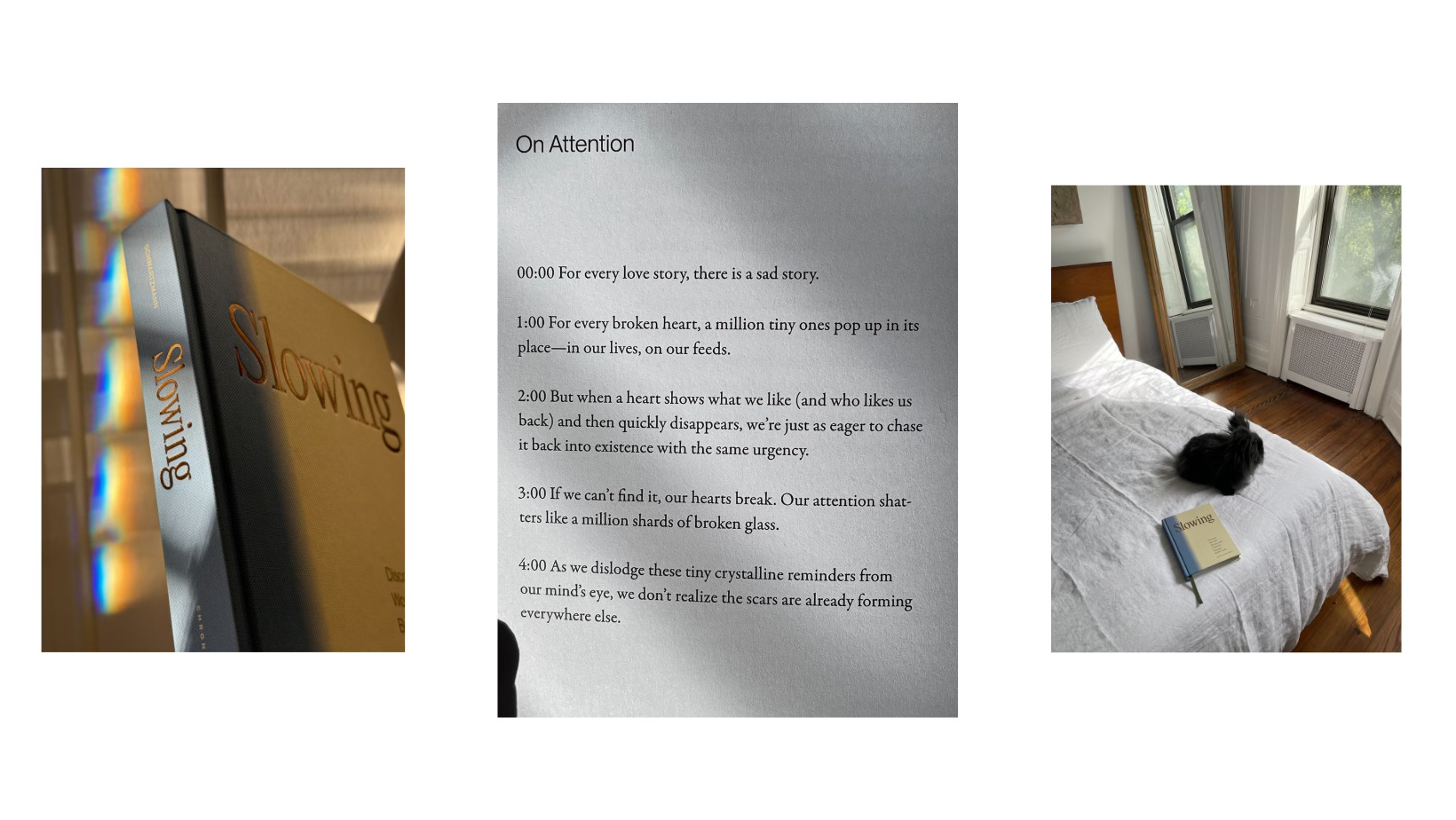

I also love that you called out the Timestamps (one of these stories is in each section of the book for those who haven’t read Slowing yet). Something I’ve learned about myself as a writer is that I really like to play with aesthetics and structures. The timestamps, in particular, felt like an homage to the original roots of Slow Stories’ podcast, which explores living, working, and creating more intentionally (in our digital age). Beyond my own work, I think it applies to how we collectively reflect and write in this landscape: small bursts of inspiration come to us on the go or in unexpected places; we can tell entire life stories in our Notes App or social feeds.

You write about your earlier years in San Francisco and Vallejo, a suburb outside of Dallas, and Queens. What is your relationship to these locations now—do you find yourself longing for them, is there one place that you feel shaped you more than the others? To what extent do your surroundings affect or influence your creativity?

I don’t have a strong pull to California and Texas, but I do think about them occasionally. Mostly, I long for the many chapters I’ve had in New York (next February will mark my 20th anniversary in the city). That said, I often reflect on my teenage years, a tumultuous but rich period of my life: I studied dance at a performing arts high school. I took art classes, went to shows and concerts. I had beautiful friendships that were inherently creative. While things at home were not the best, I cherish that time deeply and am so lucky to have spent such formative years in Queens. I had unbelievable access to cultural institutions and resources, which were instrumental in shaping my appreciation for the arts. So naturally, environment is hugely integral to my creativity.

For instance, when studying dance, I loved taking open classes at places like Steps on Broadway (a true sensorial haven!) more than performing on any stage. When interviewing creatives, I love visiting their studios—examining fabric swatches and intricate mood boards, watching light cast shadows on their work, and seeing sculptures, clothing, or paintings come to life in real time. Without knowing it, creative environments have also taught me so much about intentionality. It wasn’t until I slowed my pace and output that I could appreciate how special and generative these places are.

On your Substack, in a newsletter titled “Continue”, you mention that you have never taken writing classes. I feel like some of the best writers don’t; there is a secret alchemy at play. The essays in Slowing are poetic and incisive; you have such a distinct style of writing. How do you know when to follow an idea?

That means so much, thank you! I’ve really honed my voice and leaned into its lyrical quality while learning how to edit in service of the work above all else. There may be some things I want to say, but they just don’t fit, so I’ve learned to let a lot go (and treat “discarded” details or sentences as a jumping-off point for future ideas).

That part of my process has been a big indicator of what’s taking up space in my mind and on the page. I overwrite and then save the scraps for later. But I also just think I have pretty consistent through-lines that interest me generally. If I’m thinking about or engaging with them in my daily life, there’s a good chance I’ll want to explore them in my writing.

Other than time and pace, there are two big themes that I’m reflecting on right now, and I’ve paid quite a bit of attention to them in other ways—like sharing photos on Instagram or writing about them in ancillary pieces here on Substack… more soon!

There’s an essay in Slowing called “A Living Archive: On Taking Stock” and in it you write, “My childhood rooms were sensory dreams, but as I grew up my self-expression moved online.”

When did you first feel comfortable with the idea of an audience and how did you decide that you were ready to share your work online?

I grew up online, as many of us did, so the digital space has been both a place of familiarity, opportunity, and, in recent years, tension. But rather than thinking of an audience, I really have thought of this space for connection—and creativity. When it comes to writing, I have probably prematurely shared work online, but as I mentioned in my recent story, “Spine” (which is about fear and creative courage), I’ve never let fear or discomfort stop me from trying to make things. The internet is a canvas in some ways, and I can always change the medium if needed.

In “Drafts: On Creativity” you write, “These days, relief is the first word that comes to mind when I think about creativity. Finding myself beginning a project means there is a shape to it—even if I don’t recognize it (especially if I don’t recognize it). Writing a little every day helps. It’s akin to waiting for the shower to warm up: You know you need to enter this space, and it’ll take a moment to feel like something you can withstand.”

What calls you to sit down and write—is it ever the same thing twice, or can it be something as simple as the sun coming through your window, a song, a mood?

For me, simply thinking counts as writing a lot of the time. It’s usually after a particular thought reverberates through my body (I’ll literally get a chill or smile to myself as if I’m in conversation with the idea) that I’ll get myself set up to write for a longer stretch. I also always carry a small notebook in my bag, so that’s helpful if I can’t literally sit down and write.

But more realistically, if I’m on a deadline or need to get words down, I’ll ensure my space is quiet and primed for concentration. As I mentioned earlier, environment is a huge factor in whether or not I’m going to be productive—or distracted (while I love writing in naturally lit spaces, I also love photographing them, so my phone often has to go in another room).

On the topic of pace, output, and burnout Allison Strickland—an artist you interview in SLOWING—advises that “You cannot only inhale; you have to exhale, too. There are times you have to research and do absolutely nothing. We’re not meant to create constantly. Entropy is part of the creative process, not a hindrance to it.”

What have your moments of rest and recharge looked like lately?

I loved my conversation with Allison—so much wisdom.

Resting and recharging are entwined with the little things: long walks in my neighborhood, family hangs with my husband and lionhead rabbit, Pepper, snack sessions, or getting lost in a good book. Again, I have immense gratitude that I get to do these things so often.

Circling back to the essay I previously mentioned, “Drafts: On Creativity”, you wrote something that really made me pause: “I had reached the point of no return—creativity and technology were one.”

More and more these days, it seems that people are relying on technology to produce, or at least share, their art. I’ve asked myself this and wanted to ask you (and encourage readers to ask themselves as well): What creative activities or hobbies do you enjoy that don’t involve a phone or computer?

Reading, for starters! I am a physical book person all the way.

I’m also obsessed with my rabbit, Pepper, so I often sit with her. She actually loves it when I read next to her and will hop over to “chin” the book (marking it as hers) and then loaf out.

Hmm, what else? Going for walks, style and dressing up, seeing art exhibits…

I’m also trying to fall in love with travel again. Since the pandemic, it’s been difficult for me to experience it the same way, but it was such a big part of my life—and there’s so much I still want to see.

One of the recurring themes you discuss in SLOWING is consumption—how we spend our time, who or what we engage with, how much is a healthy dose. In “Space Beyond the Stars: On Uncertainty” you write that the digital space “takes more than it gives. It demands a perpetual statement of proof that we’re worth listening to—that we have something interesting to say.”

How do you discern what is worth spending time with? What type of online experiences lend something to your day, rather than taking away?

It fluctuates day by day. Lately, amid troubling and exhausting headlines, multimedia experiences feel incredibly nourishing. I love to look at the world—quite literally—through other people’s lenses: a photo of how someone noticed the light in their backyard. A video diary of someone’s creative practice or solo trip paired with poetic text or audio. Visual storytelling is a big part of my practice, and ultimately, I think it makes me a better observer—and writer.

Someone tells me we spend so much of our lives saying no to ourselves, you write in one of your Timestamps (I love their experimental, stream-of-consciousness form!) It’s so true. What’s something you’ve emphatically said yes to lately?

Thank you so much. Someone called them poems, which I loved!

Lately, I have emphatically said yes to coffee dates. I’m an introvert to the core, but I cherish the people I’ve connected with and the friends I’ve made through my creative endeavors. It’s always lovely to see them. In fact, one of my Slow Stories guests became a friend. She lives in Scotland, and though we’ve never met in person, we’ve had quarterly virtual coffees for the last two years.

Those who follow you on Instagram know that they can rely on you for a great book recommendation. What are you reading these days?

My TBR towers (we’ve graduated past stacks) are at an all-time high, and while it’s a good problem to have, it can be overwhelming to figure out where to start. I just finished There Lives a Young Girl in Me Who Will Not Die (a selection of Tove Ditlevesen’s incredible poetry, which is out next March with FSG), and Sophie Madeline Dess’ forthcoming debut novel What You Make of Me (out next February with Penguin Press). I also just started Blue Light Hours by Bruna Dantas Lobato, and I can already tell it will be a new favorite.

Some other fairly recent reads include The Wilderness by Ayşegül Savaş (I also loved her latest novel, The Anthropologists), Another Woman by Hannah Bonner, The Hearing Test by Eliza Barry Callahan, Honey by Isabel Banta, Small Rain by Garth Greenwell, and Madwoman by Chelsea Bieker. All beautiful and brave in their own ways.

Because you read and share so much of it, I’m wondering if you’ve ever thought about writing fiction?

I’ve always wanted to write fiction; I just haven’t been ready for various reasons. But Slowing unlocked something in me; I emerged as a different writer—more discerning. This entire experience reinforced the idea that good things take time. All of that said… I’ve been working on a novel for the past year. It’s the first piece of fiction I’ve attempted that feels like it has momentum, and I’m surprised and curious about where it’s going.

I’m just starting to get back into the groove after the whirlwind of launching Slowing (and refining another nonfiction proposal), but I’d love for it to find a home one day.

As a first-time author, what surprised you most about the publishing process?

Oh, so many things! I was lucky to have a strong handle on the marketing/PR side of things from my first life as a business owner (in the fashion/content/marketing space), which I’ve heard other authors express surprise (and, at times, dismay) over. I think what surprised me most about this book, in particular, was the design process. It was really educational.

The book itself is a beautiful object: it both catches and creates the illusion of light. How much input did you have in its design, and what were you inspired by?

Thank you so much. Light is on my mind in many ways lately… But yes, I did have quite a bit of input, and I’m really grateful for that. It was a months-long endeavor for both the interior and cover design. I learned a lot about the creative and production process, considering the book’s package from all angles—editorial, sales, marketing, and so on—and creating something that honors a collective vision. I actually traveled to Chronicle’s San Francisco HQ to meet my editor and designers in person and look at some production details, which was special.

I wrote about this in one of my early process diaries, but initially, I leaned on design because I still wasn’t quite sure of myself as a writer: I let the design “concept” serve as a scaffolding when all I really had to do was put the words down. By the time I finished writing Slowing, I arrived at that point (read: I could do this. I did it!), meaning everything had changed—including the proposed visual treatment. I had become more discerning in my tastes, but more importantly, a different, quieter tone emerged in the actual stories. I knew the visual aspects of Slowing needed to reflect this evolution.

I go on to mention in that story that by the time I finished writing Slowing, I was interested in how visuals could capture the palette of the ordinary: I thought about the colors that often make up my day: a bright morning sun, golden yellow—sometimes blinding or quietly emerging from a wall of clouds. An afternoon walk in Prospect Park, where greenery abounds in the spring and summer. Then, that blue sky—expansive and universal, up until it gives way to the blue hours of the evening, a bruised palette representative of a hard day or a hard day’s work.

The cover—the palette of the sky—encourages looking up toward the light, and the green endpapers and ribbon bookmark ground you in the stories. I think it all came together beautifully, both visually and conceptually.

When was the last time something stopped you in your tracks—where were you, what was it?

All throughout October. It’s been unseasonably warm in the city, but autumn is trying to break through—show itself off. Recently, I was walking with my husband in Prospect Park during golden hour, and I had to convince him that it was worth examining the same tree for at least ten minutes.

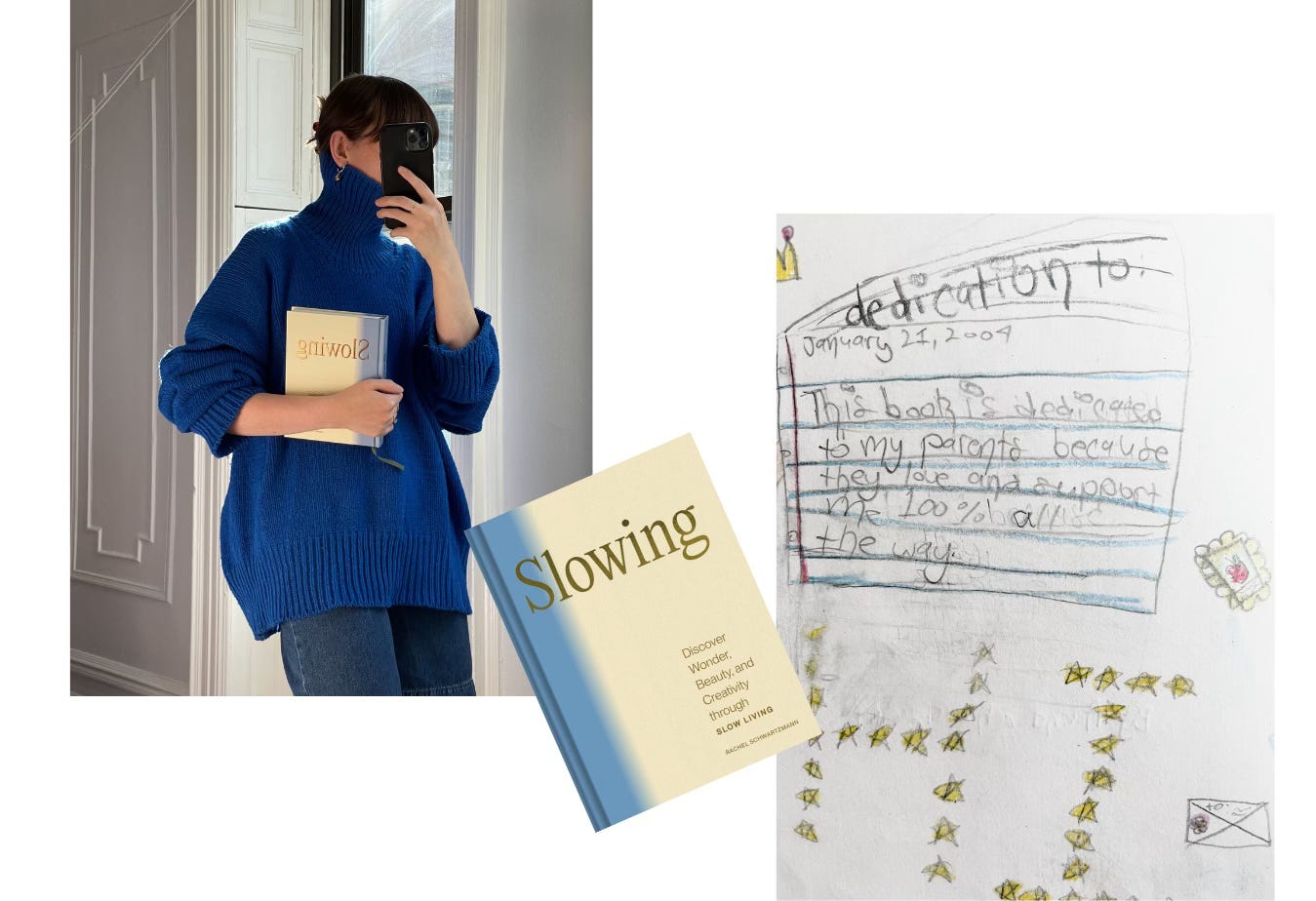

Slowing is dedicated to your parents. You’ve shared a heartwarming photo on Instagram, in your childhood handwriting, of a dedication to your parents; being an author has been a life-long dream. What would you tell your younger self about this moment of your life?

While it hasn’t always been easy between us, my parents have been unwavering in supporting my dreams. This book is a culmination of that love. Slowing was always for them.

My kindergarten school picture just popped into my mind. (It’s so ‘90s!) The background is a dark purple, marbled seamless. I’m wearing a choker and (coincidentally) a purple velvet top; my long hair is down with a single braid in the front. But my smile is really what’s worth mentioning: tight, closed-lip, painfully shy, a small front tooth peeking through. A reminder of that quiet little girl—awkward in many ways but never afraid to follow her creative curiosities. Her resilience is something I carry today. So, first and foremost, I would say thank you to her for setting that foundation. I’ve been working hard to build on it for us and am amazed at the many opportunities and experiences it has led to.

I would also tell her that it’s okay that you’re quiet—you will say things in other ways: in images, gestures, words, even silence. You don’t have to monetize your creativity for it to mean something. It doesn’t have to be perfect, and it won’t be perfect getting there. You will be in a constant state of tension—exhaustion and exhilaration, creative and crunched for time, in disbelief and clarity, moving fast and slow—feel it all. Everything you work for brings you one step closer to yourself.

From “Dawn: On Beginnings”: “I’ve come to understand that a beginning is the most private moment we can have. It’s a feeling, a hope, a gift”.

What new beginning have you found joy in recently, what are you looking forward to?

Tangibly, the beginning of winter. It’s probably my second favorite season (after autumn), and I look forward to continuing to indulge in seasonal splendor.

Regarding what I’m looking forward to creatively: I’ve mentioned this before, but the circumstances while writing Slowing were not what I expected. I was navigating a mental health crisis, and I’ve been reflecting on what this book would have looked like and felt like had I not endured those challenges. I don’t necessarily wish things had been different—because ultimately, I can’t change it, and the conditions made Slowing what it was—but it’s just interesting to think about.

So, as I look to my next (book) project, I’m eager to cultivate a creative practice with a calmer state of mind. Anxiety will always be a part of my life and story, but right now, I have a better handle on it day to day. I’m hopeful this will open up space to move differently through the work and, in turn, let myself be moved in new ways.

Rachel Schwartzmann is the author of Slowing and the writer/host of Slow Stories—a multimedia project that explores living, working, and creating more intentionally. She also writes about books, creativity, design, and fashion, and her essays and interviews have appeared in BOMB Magazine, Coveteur, Literary Hub, TOAST Magazine, and elsewhere. You can follow her @rachelschwartzmann to see what she’s reading, writing, wearing, and sharing.

To buy a copy of Slowing, consider supporting one of Rachel’s favorite bookstores: Books Are Magic, McNally Jackson, Greenlight, Green Apple Books, Bookshop.org, and Troubled Sleep (they don't carry Slowing but Rachel assures that it’s a gem!)

Interview by Emma Leokadia Walkiewicz

That really gave wonderful insight into the Rachel's writing process! I thoroughly enjoyed this :)