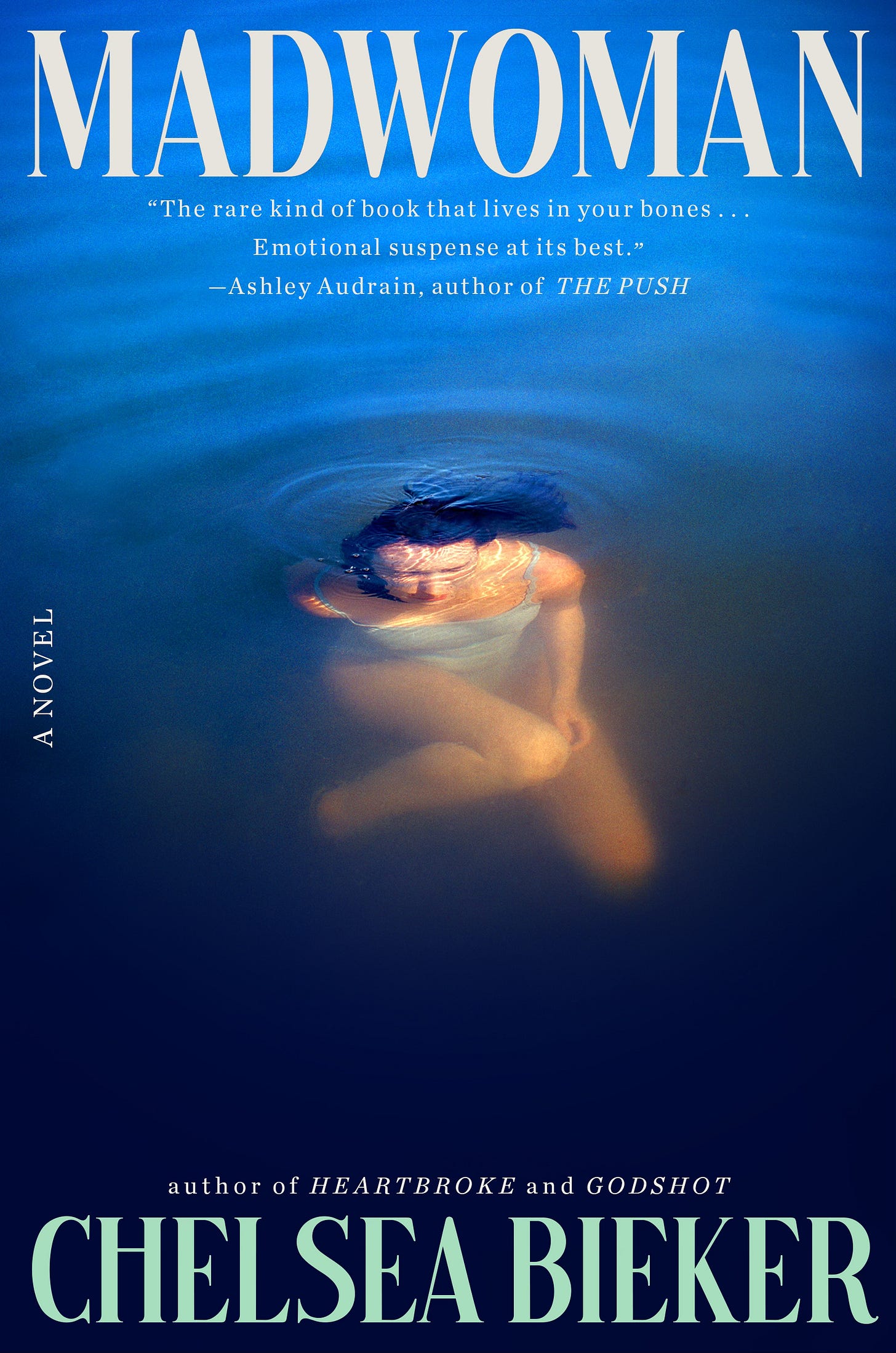

An interview with Chelsea Bieker

The author of Godshot and Heartbroke discusses her powerful new novel, Madwoman

In Madwoman, a letter from a Californian prison upends everything for a woman whose comfortable middle-class existence is a careful curation. Calla Lily has successfully slipped away from her old life, becoming Clove, wife and mother to two young children. No one—not even her loving and dependable husband who she meets during her senior year of college (“His love language was touch. Mine was secrets.”)—knows the truth of her identity or the painful details of her turbulent childhood, until a message from her mother threatens to obliterate the perfectly ordinary life she has constructed for herself.

The novel begins with a sentiment so true it’s jarring, reminding the reader that society is rigged against the very people it is meant to protect: “The world is not made for mothers. Yet mothers made the world. The world is not made for children. Yet children are the future.” With live-wire propulsion and radiant prose, Chelsea Bieker’s Madwoman is a gripping meditation on the life-long repercussions of domestic violence, an exacting portrait of modern motherhood. A searing authenticity and humor shines off every page as Bieker illustrates the isolation and struggle of maintaining one’s identity during the early years of raising children—“The thing about motherhood was that everything was happening all the time.” Bieker’s third book (and second novel) is an exploration of the relationship between child and parent, mother and daughter; the cost of that connection, the price of both holding on and letting go, the risk and redemption that comes with forging onward.

Above all, Madwoman is crucial tale of power, resilience, survival, and of how abuse, Bieker’s protagonist Clove affirms, infects everything.

What inspired your love of literature, and when did you know that writing was something you wanted to pursue?

It’s hard to remember a moment where books and writing didn’t feel vital to me. For most writers, their love of stories and books brought forth the desire to write, which is true for me, too. I have a distinct memory of being a child and wondering who wrote all the books. Being curious about authors, looking at their bios and studying their photos to glean any understanding of who they were and where they came from. Clearly they were super-human. I think I thought they were all famous people. I wondered if I could be an author but I didn’t know any writers personally as a young child. But then my aunt took to me a reading at the wonderful independent bookstore in Fresno, Fig Garden Books (now closed sadly) and I got to meet Jill Conner Browne who was writing the Sweet Potato Queens series that my aunt was very into. She was vivacious and funny and it knocked my socks off that you could just go meet her and she would sign a book for you. She’d created this whole world and a huge following of women with her words. I was probably thirteen or fourteen. It made an impact on me and expanded my mind of what was possible. I didn’t like high school. I had a hard time figuring out where I fit. I was a hardcore gymnast and just felt on the sidelines of the whole school scene because I trained so much, and I also just wanted to read novels all day. Overall the school was a toxic, misogynist environment. But thankfully one of my English teachers noticed my writing and suggested I get involved in the school paper, and that was a godsend for me because she let me write book reviews about any book I wanted. I had no literary awareness, I just read what I liked. I read everything with the same curiosity. No one was telling me like, this is literature and this is shit. I’m happy for that because I read without pretense. I looked for books that made me feel. Had heart. Made me turn pages. With the paper I suddenly had a place to write about the reading I was doing. Seeing my byline was special too. It felt like I could offer something. It set me on a path to pursue journalism and I worked on the college paper in the Arts section, but pretty quickly I knew I wanted to be writing fiction and my own essays. But I’m grateful for the start in journalism because it taught me some of the most important things I know as a writer: 1. Be ever curious and ask great questions. There’s always more to the story. And 2. I can write whenever and meet a deadline. With a daily paper there’s no waiting for inspiration to strike, you just write the damn thing. That’s a lesson that’s served me well in my fiction life. I can always write no matter what. It’s a deeply held belief.

How did the idea for Madwoman arrive?

I think the very, very first seed of this story was born from this one night I went out. My daughter was two, and I almost never left her for any reason (undiagnosed post-partum anxiety y’all!) but I went to this reading and then to a bar afterward with some writers. And there was this writer there who was younger than me, and just was so much fun and we had this great night, but I remember thinking, wow, I’m different now. It was the first time I’d really noticed the energetic change in me since becoming a mother. I was also experiencing post-weaning anxiety after I’d stopped breastfeeding and was trying to figure out what was wrong with me. It was actually a very dark and hard time and I felt a little reckless with everything I was feeling. I was struggling but from the outside probably seemed totally fine, something I’m great at. But I just came home from that night with the title in my head, Madwoman. I had this vision of two women in a car speeding toward an edge. Almost like a metaphor for the before self and after self of motherhood. I knew it had to do with that initiation, and the ways I’d changed. I wrote it out as a quick short story and put it away for a long time. I picked it back up in 2020 and it started pouring out, quite different from that initial story idea, but I think it retained the same sort of desperate, urgent energy and voice. Madwoman came rushing at me. I keep saying writing it has been one of the most spiritual experiences of my life. I think all my books are and hopefully will be, but this one felt different and it’s because I was different. I had been dragged deeper into my shadow than ever before, I’d seen things I hadn’t before seen, and I was understanding the past for the first time in new ways. I also had the confidence from writing two other books. I felt a little more in command, and in a lot more trust of my own instincts.

I’m so curious about your writing process and what those days looked like—where did you write and how long did it take from first draft to getting Madwoman to where it is now?

That first seed came in 2016 or 2017 about, and then I didn’t start writing it as a novel in earnest until 2020. I was still finishing Godshot and Heartbroke when the idea arrived, but I never forgot the feeling of the first brush with it. But I couldn’t have written this book until the self of 2020, 2021, 2022, 2023 stepped in. Because that self had more distance from early motherhood, and also I had the shock and hellish experience of both parents dying. Another initiation. I’ve been reborn about forty times over the course of writing Madwoman. It revealed a lot to me about my own past and life. I wrote it fast and furious. I think the very first push I did 1000 words a day (which more often looked like 2 or 3 thousand words a day) and then there was a moment in 2022 where I woke up and understood the book in its totality. I ripped out the entire back half and rewrote it. It was an incredible moment because I knew all my showing up for it day after day had arrived me at this deeper understanding. The book changed a lot, got twistier, and got truer. I really want to underscore that I see myself as a channel. I know this book needed to come through me and I was at its mercy. The coolest feeling of my life is that feeling when a solution comes, or a realization comes and it’s like wow, I touched something that is of me, but not totally me. I mean, everything is connected, but I have to be clear and open for the message to come through. The greatest high.

“I really want to underscore that I see myself as a channel. I know this book needed to come through me and I was at its mercy.”

—Chelsea Bieker

Your characters are so vividly rendered—you’ve built this incredible psychology and history for each of them, right down to Clove’s mother-in-law, Tootsie. (Even Jane’s Chevy has a backstory!) How do you know when you’ve got a character? How do they arrive to you and how do you know when they’re complete?

I’m curious and paying attention. I am just desperate to know about peoples’ lives. I love asking questions. I want to know what their pain points are, and I want to know why they think the things they do, I want to know how their marriages are working ten and twenty years in, really. Like, do you believe in souls? Like, have you had an encounter with an angel? I don’t understand small talk and I hate it so much. I’m like please tell me about your childhood, the ghosts you’ve seen, tell me the most tender moment you’ve ever had, what are your absolute dreams, what is something your mother told you you’ll never forget? Fuck, life is short, you’re really asking me about the weather?! (Laughing). Every one of us is carrying a story, we have a backpack of stuff, sometimes a trail of luggage. Some are more awake to it than others. I get that. But I strive to be awake. It’s the same with characters. It makes me crazy when characters are described like, turning on their heel, and all these common physical movements in lieu of what they are thinking and feeling beyond the general obvious stuff. When I write it’s impossible for me not to employ that curiosity. It’s complex! It’s more than one thing. I’m also sometimes exploring things I sense in other people but are not articulated. The page is where I can get to that juicy dialogue or confrontation or honesty that isn’t always possible in our actual lives. It’s just not. There are some conversations I’ll never have and that’s more than okay. Sometimes that’s about safety. On the page I can ask and do anything. I want to make fiction and read fiction that is testing those edges.

Madwoman has one of the best openers I’ve ever read: “The world is not made for mothers. Yet mothers made the world. The world is not made for children. Yet children are the future.” How did you decide on this opening—was it what you had in mind from the very beginning?

Those lines were always there but not always as the first lines. For a while I fussed with a different opening figuring out how this character would announce herself. But then I just pared it down and went with that. I think I had a subconscious fear (now conscious) that if I started with those lines people wouldn’t be into it, because patriarchy affects us all, and patriarchy hates women and especially hates mothers. So I think I was like, is there a sexier opening? But no. There’s not. That’s a provocative powerful opening that I hope makes people think. It’s also got style and rhythm, something that is non-negotiable for me. But I mean, those words. I decided to step out boldly with them. Any mother reading those words who is awake to the world will be like YEP. In early motherhood I felt like a pariah. Mothers get pushed off to the side to mommy groups and parks. I went into a grocery store and the cart didn’t have a kid seat in it. I went to the front and was like, do you have a cart with a kid seat, like what am I supposed to do here with these small human beings with me while I shop, pray-tell? And they were just like, sorry we don’t have that. I was stunned, but honestly, not surprised. (They closed down maybe because no one could shop there with their kid in tow.) I encountered shit like that all the time. The post office scene in the book is a very real scene that happened to me, and I had a very real breakdown in the post office. Just exasperated. I remember feeling like it would be easier to just stay in my fucking house. It was very defeating. But ultimately I refused to go along with that. Kids are humans. Mothers are humans. America makes things hard in a thousand ways, but to any mother who’s gotten the side eye in a line because your kid is being wild, I’m here for you. This book is here for you.

“Kids are humans. Mothers are humans. America makes things hard in a thousand ways, but to any mother who’s gotten the side eye in a line because your kid is being wild, I’m here for you. This book is here for you.”

—Chelsea Bieker

Madwoman is dedicated to your mother, “who lives in every line.” You include a portrait of her, which feels so intimate, as though the reader might recognize something in her gaze, her expression. Can you share how you chose the quotes that introduce the novel, and what the dedication to your mother means to you (and what you hope it might mean to readers)?

The book could only be dedicated to her. It’s all about a woman desperately wanting to be known by her mother. I too felt desperate to be known by my mother and exhausted from all the ways male violence made that impossible. That’s it—that’s what the book is about. How male violence comes between women. My mother couldn’t be a mother because she was under the thumb of a total and complete control system that dominated everything. It’s a tough truth that no one wants to look at. They want to be like oh, she chose a life of addiction. I mean…why can’t we look at the missing piece? But, you know, DV wasn’t even criminalized until relatively recently.

The quote that opens the book is from her journal. I had a W.S. Merwin quote for awhile only because she had sent me the poem Separation once in a letter. But when it came down to it I decided that her words were enough. No need for another voice to supplement it. She writes, prays, that I won’t end up motherless like her. It’s from an entry where she knows something terrible is coming. She is fearing for her life. She was a beautiful writer in her journals. She gave me permission to use her words in the epigraph. She wanted me to read her journals even though they are traumatic to read. She wanted to be known and she wanted the truth known. I understand the feeling expressly.

Clove is a mother of two with a degree in creative writing. She hasn’t written much at all since becoming a mother, until a letter arrives from the Central California Women’s Facility. This line struck me: “The thing about motherhood was that everything was happening all the time.” How do the demands of motherhood influence your own writing?

Motherhood touches every part of my life. My kids are always on my mind, and when I’m away from them I feel the thread connecting us strained and it’s uncomfortable. I couldn’t have wrapped my head around that prior to becoming a mother. I love this essay by Claudia Dey which says it all perfectly. You just can’t know how deep it runs. I’m sensitive too. My experiences as a kid inform the kind of parent I am and the sorts of bonds I want to have with them. Part of that means I really show up to everything. That means a lot to me. But even if I’m at a residency (only done that once) or having a mini writing retreat, I really have to work to let go of my anxiety of not being with them. I can do it, but it’s not easy. I recognize that this is a phase of life that will change like everything else. One day they will be adults. It won’t mean I won’t worry any more. But you know, it will just redefine itself. There won’t be so many practical negotiations of who’s taking care of who. Right now I’m considering my answers to you with the din of my kids playing in the background. I think in early motherhood I was panicked that I’d never write again and so I wrote under the most insane conditions with little sleep and all the things. Now I require more ease, and I guess I’ve earned that. My oldest is ten. I need more spaciousness now, longer stretches of quiet, but when they were little that was not possible for me. Some people have their moms around to help or can afford a nanny and that just wasn’t my story at all. Motherhood is so under-supported in our society, too. It’s very easy to feel isolated in it. But even still, I love it. It can be so damn hard, but I love being a mother and an artist. It feels really redemptive to me. My kids bring me closest to the fundamental essence of love that we all are. When I’m with them, I’m like, oh yeah, shit on the internet doesn’t matter. That (whatever marker of success) doesn’t really matter. What that person thinks of me definitely doesn’t matter. Love matters. I would have at one time thought that was cheesy, but now I see it as the most fully expanded version of me possible. Loving myself, loving others. Being a part of this great cycle of birthing, and caring, and loving, and creating. That’s what I want to touch in my lifetime.

You write a fantastic Substack called “Make Up Your Life”. On it earlier this year you shared that Madwoman “feels like the deepest and most emotional thing I’ve ever written” and that “there was so much intensive exploration going on—of self, of the past, tearing apart the stories I’d told myself, and getting closer to the capital T truth of things.” As a writer, how do you decide what material from real life to use in your fiction, and how does the idea of an audience affect how much or how little you choose to include?

It's all blended and nearly impossible to parse out what’s “real” and what’s not real. I’m writing from an emotional truth at all times. I thought it was funny that some people thought my first novel Godshot was a memoir. But maybe it read that way, I don’t know. I wasn’t personally in a religious birthing cult as a teenager. I didn’t have a baby at fifteen. I didn’t personally have a pastor who wore golden robes. But it’s all representative. I did grow up in the Baptist church and absorbed the wonky ass messages about women there. I did experience abuse and neglect as a child and that novel deals with that. With Madwoman, no, my mom didn’t go to prison for murdering my father. The plot of Madwoman is wild! These big things didn’t happen to me, but the seeds of all of it is true to my heart. And then some stuff is real but few people would ever know. Some of my family reads my work but we don’t have terribly in-depth conversations about it. I don’t always know what they think and I’m fine with that. Family is hard. It’s like, just tell me you liked it, and if you didn’t, keep that to yourself. But I imagine it’s emotional in different ways for them. I had one family member who had a very strong reaction to my short story collection and disowned me and said she hated me. I thought this was plain awful that she did that, but in some way I understood. She’s not a reader, she didn’t understand what it was she was reading, and the stories brought up uncomfortable feelings for her, and she didn’t want to have those feelings and sort of directed that anger at me. She saw herself in the stories in ways I could have never predicted because art is inherently confronting. You can’t predict how art will jar someone. Honestly losing that person felt weird in the moment, but in truth she wasn’t a part of my life and hadn’t been for decades. It was sort of like okay. I feel for her because we’re part of the same lineage of trauma, and I get it. But it will never change what I write or how I write it. I write with the highest love and intention for all in mind always, and I could really drag some people, but I generally do not. People think my work is dark. But oh, it could be so much darker. I’m actually really quite nice in my work. I’m interested in the ways art can challenge the wild ways family systems protect abusers. I’m so fucking tired of that! That essay from Munro’s daughter Andrea Skinner was so stunning. I was like, fuck yes, tell this story. It’s the anecdote to shame.

The novel has such a cinematic quality to it—I’m excited to see this adapted into a miniseries or movie. I’m curious if you ever think of that while writing, the idea of your work being adapted to the screen, and if so does it affect how you write scenes or what you include?

Thank you! I take these walks where I play music that reminds me of the project and I just watch my mind movie. So I see everything very cinematically. I too am waiting for someone to make my work into a movie. Let’s light a candle for that.

So much is discussed about the writing of a novel; I'm eager to hear about how the editing process was for you, and how it feels as a writer to have other hands touch your project.

I just know when something isn’t working or could be better. It’s just a sense. I know it, and it’s up to me to fix it. An editor can point out blind spots. I have a really amazing writing group I share everything with and I trust them implicitly. I trust them to ask great questions, and to be like, yes, you’re doing it. But I do believe we all know the truth of our own work. It’s a problem when too many cooks are in the kitchen. You have to hone a self-intimacy and self-trust above all. With Madwoman, lots was cut. A good agent will prompt the right questions. Because the book can start out as one thing, and mid way, reveal itself to be another. But I love when that happens. When the project itself turns around and tells me what it’s about. Chills. I live for that.

“On the page I can ask and do anything. I want to make fiction and read fiction that is testing those edges.”

—Chelsea Bieker

Which books (or movies, articles, etc.) impacted you while writing Madwoman?

I tried to touch base with the stories of my childhood where I felt the most understood and my favorite movie as a kid was Sleeping with the Enemy. The woman escapes her abuser in the end. Me and my mom cheered. It was hugely impactful, because it helped me know what we were experiencing was not okay, and also that other ways to live could exist. I also read all of Lenore E. Walker’s work on domestic violence which was pioneering for the 70s, and I think Animal by Lisa Taddeo helped me to really feel into female rage and to feel fearless on the page. That novel doesn’t hold back at all. That’s the kind of book I want to always be reading.

As a follow up, can you recommend three books either similar in tone or content that a reader might enjoy after finishing Madwoman?

Animal by Lisa Taddeo, The Push by Ashley Audrain, and Black and Blue by Anna Quindlen.

I want to talk a bit about what promoting your work as a writer in this specific moment of time feels like. Writers twenty years—even a decade—ago didn’t have to deal with the immediate opinion of readers and critics, while simultaneously having to promote their work online. Was there ever a hesitation to engage with your audience on platforms like Instagram and Substack? What is your relationship to this connection?

Hmm. I envy writers of yore who didn’t have this added layer honestly. I think for the most part, social media becomes a huge distraction and barrier to creativity at its worst, and at its best, sure, we can connect in a great ways, and meet people we wouldn’t otherwise but I’m suspect about it in terms of actual creative process. I really have to go through times of totally not logging on at all because I start to just have these images and voices in my head. I have to connect back with myself. What do I really like? When I take it away suddenly I’m much more creative on every level. Even what I wear feels more clear. I’m wearing what I like versus what I’m being told to like. That said, it’s beautiful that I can have a direct line to readers. That is incredibly special to me. Substack is really cool and I love it the most actually. I’m newer to it but it’s like old school blogging but better. I want to take in and make deeper content. I hate now how everything on Instagram is a video. I want to see an image and read about it. I don’t want these clips. Whatever. At the same time I participate in it because that’s what I can control myself and I do think that we can’t pretend it doesn’t matter. It’s just a part of it now. If someone is going to publish me, I’m going to do everything I can to amplify that. I try to ask myself how can I do this authentically to me? How can I share messages I really care about it? It has to feel aligned. But sometimes I fantasize of being a writer in the age of Kate Braverman and Mary Gaitskill. The age of the physical fan letter a rave NYT review leading to massive sales. I also have concerns about art being dictated by the consumer which should never ever happen but is happening. Art should always be setting the tone. Not the other way around. But I think social media makes it possible for everyone to have a platform and say. Is this a good thing? I really don’t know.

I feel like this might be a fitting question to end with: What does the beginning of a project typically look like for you? How do you know when to follow an idea? What excites you most about writing fiction?

Each book has looked a bit different. With my newest novel I’m currently writing, I felt the strong sense to journal and “collect” and “take it on walks” every day, but not sit down in front of the Word doc yet (or Scrivener in this case). I was in a phase of visualizing, of connecting dots, and following impulse. This period lasted a few months and then I sat down to start writing it last September. I am a writer who really trusts the process of once I feel that heat of a bigger story, then I know more will follow if I remain open. Maybe people want a more technical answer but I don’t have one. It takes a lot of blind faith. A dash of delusion. A bit of swagger.

Chelsea Bieker is the author of the debut novel GODSHOT which was longlisted for The Center For Fiction’s First Novel Prize, named a Barnes & Noble Pick of the Month, and was a national indie bestseller. Her story collection, HEARTBROKE won the California Book Award and was a New York Times “Best California Book of 2022.” She is the recipient of a Rona Jaffe Writers’ Award, as well as residencies from MacDowell and Tin House. Raised in Hawai’i and California, she now lives in Portland, Oregon with her husband and two children. Her newest novel, MADWOMAN, is out now from Little, Brown and Oneworld in the UK.

To buy a copy of Madwoman, consider supporting one of Chelsea’s favourite book stores: Broadway Books Portland (for a personalized copy!), Powell's Books, Books are Magic, Annie Bloom's, Queen Anne Books.

Interview by Emma Leokadia Walkiewicz