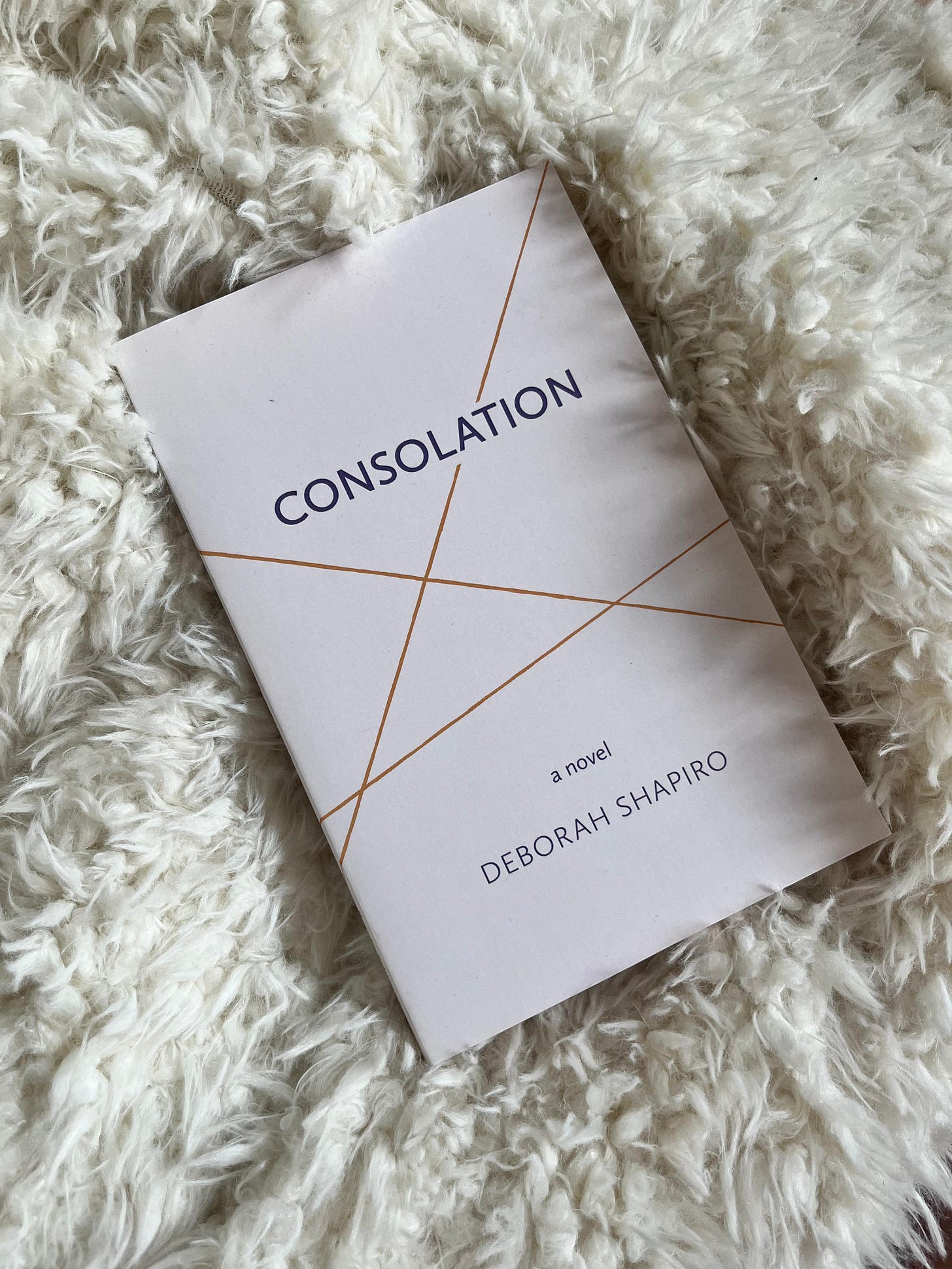

An Interview with Deborah Shapiro

Musing about the ghosts of December over a perfect winter book, Consolation

“Days of clear brilliance,” LM Montgomery writes of December in The Blue Castle, “Evenings that were like cups of glamor - the purest vintage of winter's wine. Nights with their fire of stars…”

At night I’ll lean out the living room window, the apartments across from mine dark and sleeping, tilt my head towards the skeletal oaks - who resemble old women snarled in their own knitting, as Linda Pastan describes in her poem Blizzard - and inhale the air. I do it again and again, like it might be the last time. I want to remember this smell, or maybe it's the sensation: There is a sharpness that can only found in December, both a warning and a sweet hush in its note as if to say I could kill you but I also cradle your memories. I live not far from a cemetery where a number of relatives are buried, blocks away from the first house I lived in, as well as my late grandparents’ home. I am reminded of childhood, freezing cold winters, death: in other words, vulnerability. Out the window past midnight, when the cars passing by are few and no one is making noise, I return to something. Weren’t they wrong, after all, to convince us that the veil is thinnest in October? December is a ghostly month.

I think it’s fair to say that Consolation, the novel by Deborah Shapiro, has a ghost at its centre. The main characters - Justine, Marina and Holly - are haunted by the sudden death of James, a photojournalist each was, in varying degrees, connected to. Though we as readers know James only in absentia, we feel the longing and electricity in Justine’s first encounter with him, rosy-cheeked on a frozen lake, the thrill of a hand held at an age when she doesn’t yet know how to hold herself. After exchanging numbers with James following an introduction that feels fated, Marina searches his portfolio online, regarding images of people rendered in the close-up of chaos, while her greatest work - a manuscript which garnered a few exclamatory emails from editors - remains an icon on her desktop. His aunt Holly, a former Juilliard grad turned social worker, was an omnipresent figure during his childhood, a time when he was a sly-looking boy with brown-gold eyes. Though James is the axis around which the story revolves, the three women left to mourn him - with their vast, complex inner worlds - are the heart and soul of Consolation.

One of my favourite scenes occurs later in the book, when Justine and Marina are sitting under a bright blue sky, in the fading green of Central Park:

Even as the sun sank westward, the day would remain warm into the evening. It was early fall, but summer’s heat was hanging on and they were two women on a rock in the middle of the city. Maybe it was the turn their conversation had taken; ever so briefly, the who and the where and the when of herself slipped away for Justine. The precarity, whose hum had grown louder since she heard about James, was silenced.

A few sentences later: Off the rock, along a path, out of the park. They took the Fifth Avenue bus downtown. Next to each other in two seats, Marina at the window, Justine by the aisle.

There’s a vivid cinematic quality to Consolation. I’m curious as to what you watched or read while working on this book. Which films or novels or poems or music - or experiences - informed the book’s tone?

Deborah Shapiro: I love this question because so much of this book has to do with atmosphere and tone. A big influence for me here is Chantal Akerman. I’m thinking of her movies, certainly, and how they ingeniously explore the passing of time and movement within spaces, but also the books she wrote – My Mother Laughs and A Family in Brussels. They capture the rhythms of ordinary life so well.

When starting on Consolation, I was specifically inspired by Natalia Ginzburg’s Happiness as Such, which is built around a character who is absent – we encounter and learn about the other characters in the novel through their relation to an absence. I thought that was an interesting, revealing way to structure a story.

There's a story in Kathleen Collins's collection Whatever Happened to Interracial Love? called "Broken Spirit" in which a woman picks up a newspaper and finds out about the death of a man she was casually involved with and she thinks of an Edna St. Vincent Millay poem. It's such a distinctive moment. Collins was also a filmmaker. Her movie Losing Ground is wonderful.

For emotional acuity and getting at the gravity and significance of seemingly small moments or gestures, I always go back to Elizabeth Bowen. And then there’s Marguerite Duras, who is one of Marina’s favorite writers. Her work is so cinematic, I find, and she also wrote and directed films, of course. I re-read The Lover while working on Consolation and read other books of hers. There’s a dreaminess about her fiction that I probably hoped would seep into my own work.

But to balance out that dreaminess, I would turn to Helen Garner, whose writing has an incisive zip that I love. It’s the same with Bette Howland. I remember reading Howland’s Calm Sea and Prosperous Voyage, while working on this book, and being struck not only by how attuned she was to patterns of speech and the rhythm of language, but how visual a writer she was. Her imagery is so evocative and exact. You’re in it.

What does a good day at Deborah Shapiro’s writing desk look like? Are there certain conditions - like the weather or your mood - that are more conducive to producing work that you feel proud of, or can build on?

DS: It’s not always a desk! Often, with this book, I was on the couch with my laptop or propped up in bed. Wherever I could get comfortable. Much of it was written during the pandemic, when everybody in my family was at home. (I was very lucky to have space and a kid old enough to do remote learning largely on his own). Mostly what helps me is relative quiet and a good stretch of being undisturbed.

I’m in awe over the fact that you started your own imprint, B-side Editions, to bring Consolation into the world. What surprised you most (or what did you learn about yourself) during this process? What were the benefits of forging an independent route?

DS: Thank you! There are so many factors that go into which books get published (and then get promoted and paid attention to), factors that don’t always have to do with the quality of the work itself. In my experience, it’s like the stars have had to align for my books to be published and I just got tired of waiting for them to align for me this time. Starting B-Side Editions has been a bit of an experiment, with a definite learning curve, but I’ve really been into the whole process, figuring out how to produce a book and get it out in the world in a satisfying, thoughtful way. (It’s a very different headspace from writing.) There’s a level of immediacy and control that I’ve appreciated. I’ve honestly been surprised by how receptive and supportive people have been, from book sellers to readers to other writers – it’s been amazing and very gratifying.

In a dream movie adaptation of Consolation, who would you cast (living or dead, from any era) as Justine, Marina, Holly and James?

DS: Such a cool question but I’m having a hard time answering it! I have a pretty clear idea in my mind of what these characters look and feel like, how they move through the world, and no one is leaping to mind, though plenty of actors could embody them beautifully.

How old were you when you knew that writing was something you needed to pursue? What advice would you give to someone working on their first novel/navigating the publishing industry?

DS: I was always writing in high school and college, but I think I was in my early twenties when I started to seriously pursue it. And by “seriously pursue” I mean: trying to establish a writing life – creating conditions for yourself in which you can prioritize reading (because so much of writing is reading) and carve out time for your work, whatever that looks like, whether it’s nights and weekends or early mornings. Having some kind of community is also so important, at all stages, whether you’re working on your first novel or your fourth. Connecting with other writers you admire and respect, whose judgment you value and who’ll read your work and provide you with some sense of validation, some sense that what you’re doing matters. You can make those connections through the MFA route, but there are other ways (I don’t have an MFA). As for navigating the publishing industry, it’s never been easy for those of us writing literary fiction, but I think it’s become even harder. I really wish I had better advice to offer there.

There are endless adages from various authors suggesting that once the book is in the wild it no longer belongs to them - it adopts a life of its own. After spending so much time with them, how do you feel now that these characters are unleashed to live in the ‘real world’? Do you sense a distance? What’s your relationship to Consolation post-publishing and what, ultimately, is your hope for the book?

DS: I love these characters and still feel close to them. While readers don’t necessarily need to love these characters, I do hope they like spending time with them and that the book itself is good company. Someone asked me if Consolation would be “too sad” for them, given the subject matter. I think there’s a certain to sadness to everything I write, but I’m also interested in how sadness is intertwined with joy, with understanding, with happiness, with anger, all of it – the complexity of our emotional experience of the world. Another writer told me that reading Consolation made them want to write – I know that feeling and it’s maybe the highest praise. When you experience a work of art that really moves you – regardless of what it’s “about” – it’s life-affirming, right? Ideally, my hope is that people connect with it on that level.

Buy a copy (perfect time to buy one for a friend too!) of Consolation here, or from one of Deborah’s favourite local shops, listed below:

Thanks for the update.