An interview with Joni Murphy

The author of Barbara on the obstacles and intimacies of writing historical fiction: "We are constantly brushing up against the past."

Joni Murphy’s Barbara is a novel that lingers in mind, casts a spell, calls a reader back through time.

“To feel the subtle grain of a moment, that is the goal, to be present. I roll my thinking back. I return the years of sensation and numbness, the deaths and repetitions on their reel. I start again.”

The year is 1975: Filming a western in a town hovering above the Rockies, we meet a forty-year-old actress who is overturning the boulder of her past to reveal and examine the impressions left behind. In reading Barbara, one can hear the click and whirl of a film projector as they embark on a retrospective so textured it will arrive as a shock that the novel’s star and supporting cast are entirely fictional.

Under Murphy’s remarkably conversant eye, a bygone era of cinema, romance, travel and artistry comes to life in breathtaking detail. There is no such thing as an inconsequential object or minor character—fleeting figures are considered with as much care as lovers and parents: a costar from Texas learned how to saddle a horse and handle a shotgun growing up, but all he’s used his knowledge for is to act like a cowboy in movies. An acting teacher is not only a person but a place in time, a practice, a state of being, instructing her students to wear your character’s thoughts like a perfume.

Incisive as it is captivating, Barbara captures what it meant to exist as a woman and artist during a specific moment in the twentieth century, in a world where life was a performance and performance was life.

How long did you live with “Barbara”—and how did she first present herself to you?

I’ve wanted to write about the many layers of film for many years. My desire was to write something that intertwined the process of art making with the ‘finished project’. Before I really thought about an individual character or narrator, I was writing about independent filmmaking as an artform and a business. I wanted to understand it in relation to American history in the 20th century.

Over time, I began to feel like the story was coming from a singular voice, rather than from an external point of view. I resisted, for maybe a year, writing from a first person perspective. But eventually a very internal, feminine voice insisted on telling this story. What became clear in my mind was an image of an actress in the 1970s, a ‘modern’ woman of her time, going through a process of imaginative time travel in order to play a role of a woman who existed a century before. I was imagining a woman in the 1970s who was in turn imagining a woman in the 1970s. Film was the medium that made sense as a way of talking about history.

In 2018, before I had really started work on Barbara I remember telling a writer friend about this plan. I was excited. I remember he just sighed. We talked about all kinds of difficulties related to film being a subject of fiction. Remembering that encounter I think now I should have paid more attention to my friend’s sigh.

Can you describe how it felt—the early drafts, dreaming up where Barbara would go—coming to know the actress and the world she inhabited as you were writing?

It felt like I had a secret place I could go whenever I wanted. I allowed myself to write very intuitively. I wrote whatever felt good. I watched whatever films came up in my research. I tried to let the pleasure of writing be the guiding principle.

“There was a moment in Connecticut, after all the convincing, when I found myself alone. I stood looking at myself in the mirror, the blackness of backstage creating a dark universe all around. I told myself, if this is life, if you are already going to spend your time bleeding and crying, at least make it interesting to watch. Make it visible to others. Show yourself. That is the art and the work, to become visible and then withstand the forces of all those penetrating eyes. You have to do it fully or pack it in now.

So, I became a girl who threw open unfamiliar doors and made those on the other side pay attention. And I did it without them knowing I knew. That was the real trick, to appear innocent while working with all my young force.”

—An excerpt from Barbara

Looking back, when did you first realize that writing was something you wanted to pursue? Which authors or poets most inspired your reading and writing sensibilities?

I was homeschooled for most of my childhood, not for religious reasons but for my parents' hippie, counter-cultural reasons. I’m dyslexic and they weren’t satisfied with what the local school could provide in terms of support. It’s always a bit weird to bring this up, especially given the ways the politics of homeschooling has developed in the United States in the last few decades. I have a lot of complicated thoughts about this subject that can’t fit in this interview but I do think my experience outside of a traditional primary school education is what brought me to writing.

My mother had studied art at university, and most of her friends were artists in various ways. I grew up in an environment where making things was very much encouraged. Through visual art my mother got involved with the theater at the local university. At first she volunteered us to work in the costume shop and later on she did some part time work making props and doing set decoration.

I found my way into writing through theater, through scripts and rehearsals, costumes and makeup. I have vivid memories of listening to these college students perform very classical works—As You Like It, Cyrano de Bergerac, Oedipus Rex— in a dark theater in our Southern New Mexico town. That was my foundation both in that it gave me this sense of the vast, hidden yet accessible universe that is literature as well as showing me that art making was a way of life. I saw adults who were spending their time creating.

Even though that was my foundation, I didn’t truly embrace writing fiction until I was in my late 20s. That was the point when I finally allowed myself to admit to myself my love of writing, of fiction itself. It was a time when the art works I’d been taking in for years kind of crystallized into something that I could do something with.

There’s something very powerful about those moments when you experience an artwork at the right time in your life, when your life experience melds with something that another person has made, years, maybe even centuries before you existed. For example, I remember reading Siddhartha by Herman Hesse when I was 14, and that was the right moment for me, as an adolescent, to read about meditation, consciousness and suffering. I needed those words right then. Similarly, I don’t know if I would have become a writer if I hadn’t read Roberto Bolano’s 2666 one spring, when I was 28 and living in Vancouver, British Columbia working a coffee shop job. I experienced a kind of chemical reaction between Bolano’s words and my environment, the landscapes he was describing and the thoughts in my head. From this experience I suddenly realized I wanted to be a writer and nothing else.

How would you describe the atmosphere while you’re at work, what do you consider an ideal writing day?

The best writing days come when I’ve been working on the project for some time and I understand the world, but the frame is still open. I love those moments when a new image or scene comes to me and I get the sketch, or the pivotal phrase down on paper. I have spent months working around these little fragments that came in a flash.

The flashes are the most exciting experiences, but I need both the dramatic days and the work days that surround them to make the total piece.

Readers truly enter a world in this novel—everything is so authentic and of its time, down to the details of which products the characters use (Coty L’Aimant perfume, Postum), the cars, the material of the clothing they wear… In that regard, what was fleshing out the world of Barbara like? Did you discover anything that took you by surprise, or sent you down a rabbit hole?

Something in this question is about materiality. This is one of our society's grad school words of talking about people and their stuff, what people make and have, use and leave behind when they die.

One set of my grandparents drank pot after pot of weak Folgers coffee, while the other set of my grandparents drank a single cup of Postum in the morning, and then one after dinner, with dessert if my grandmother made any that day. The Folger’s drinkers complemented their morning ritual with a cigarette, windows closed, AC on high. My mother always drinks ‘regular’ black tea. She prefers the nicer brands they sell at the health food store. She prefers the tea that comes in a bag. Now, in the present, I make myself a cup of matcha with oat milk every morning. Mine is the drink that is currently the butt of jokes about delicate urbanites.

If I concentrate I can conjure memories of all these different drinks, how they smelled, the cups they were served in and all this has to do with identity and location, history and class and the global trades of food and drink.

I live in a building built in 1960. My favorite pair of jeans were made in the late early 1980s. Many films I love were all made in the 1970s. My grandparents were all born in the 1920s and their outlooks were all shaped by depression and war.

I say all not as to fetishize the past but rather to acknowledge and make plain how I conceive of Barbara as a work of ‘historical fiction’. Even though I did not live through the 50s I have been raised and taught by people who did. I sense the texture of other pasts through the words and habits of other people. We are constantly brushing up against the past. We live with structures, institutions, and thought patterns made in the past. As I wrote the book I tried to be sensitive to these encounters. I tried to steer clear of the cliche versions of years or decades as much as possible instead I tried to hone in on the kinds of physical textures, I myself might remember from my own life before right now.

“There’s something very powerful about those moments when you experience an artwork at the right time in your life, when your life experience melds with something that another person has made, years, maybe even centuries before you existed.”

—Joni Murphy

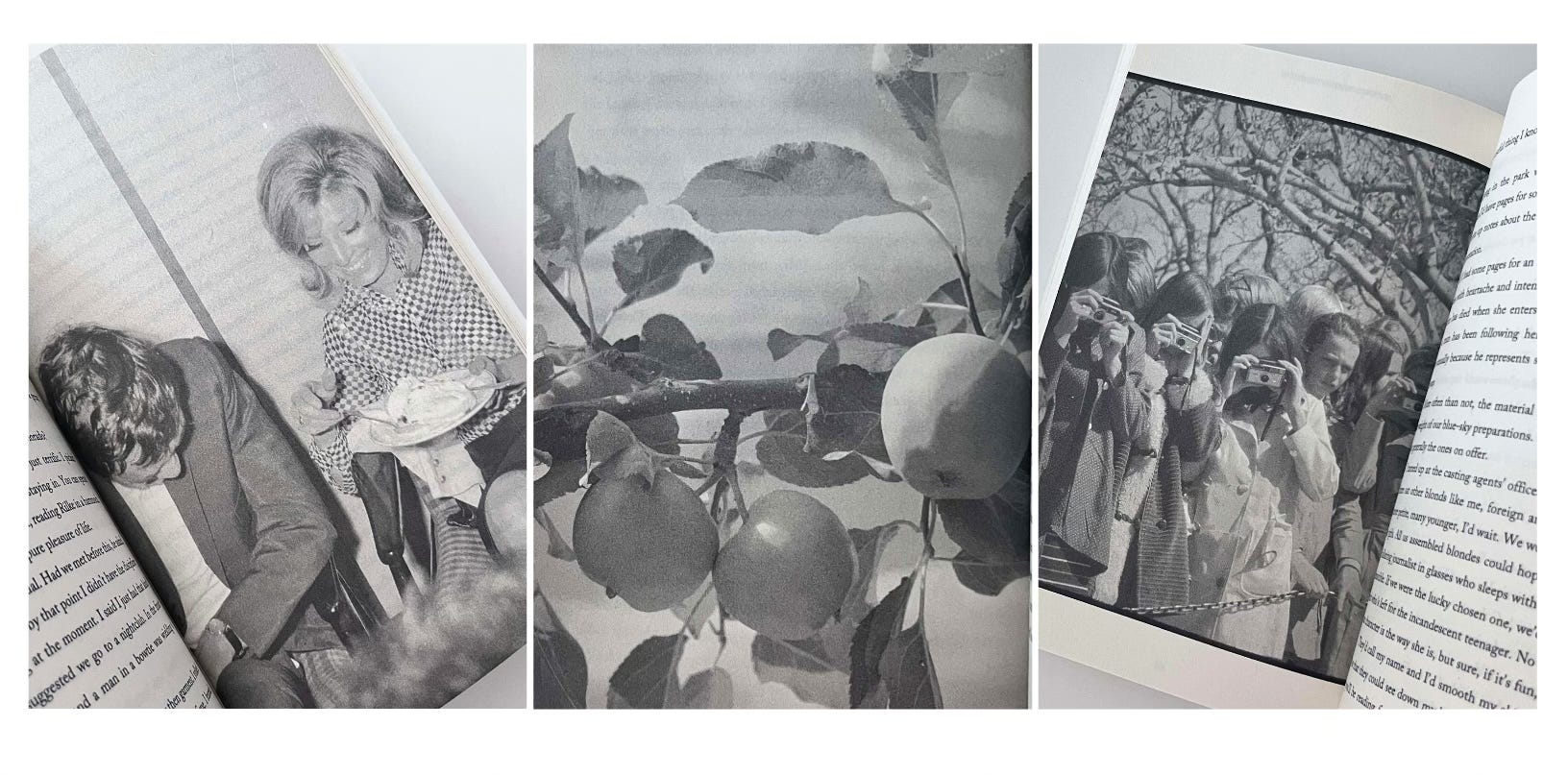

The photos that appear in Barbara lend so much to the atmosphere of the novel. I especially love the one of the group of girls holding their cameras. What made you decide to include these photographs—how did you choose them, and what do they mean to you?

The images were so complicated but I am happy with the way they turned out. All the images in the book are there because they fulfilled three necessary criteria. Each image had to be available, meaning it belonged to me or was in the public domain. Each had to be from the time of the book (none of the images were taken after 1975). And aesthetically each had to communicate the right feeling. I played with many different possible photos as I was finishing the book, but these were the ones that met all the criteria.

I also really love the one you highlight (you can see it here). It’s a photo of spectators taking photos at JFK’s tomb. Not only do I like the image itself, I also find the meta conversation compelling. John F. Kennedy is widely understood as the first president to really understand the modern media landscape. He was the first cinematic, TV president. So much of his political career, up to and including his assassination, flowed through cameras. In this image we see that even years after his death, his tomb is serving as both memorial and set for further picture creation. I do, also, love that the cover of Barbara is a picture of Marylin Monroe. Her image contains and wraps around this photo, which is indirectly a portrait of his eternal flame.

Writing Barbara inadvertently made me into one of those people who has big opinions about the Kennedy family. I’m only kind of embarrassed about this.

“The camera is like a bomb. It is like the core where the chain reaction occurs but it is also like the blast flash. No one is meant to have too much exposure. It can be lethal. The camera penetrates not only people but the material of the world. Trees, houses, people walking across a bridge, and the bridge itself. The camera’s light catches even those far off horses that were, only a moment before, grazing peacefully in their field. The light penetrates through the skin but also caresses the surface. A blinding light flashed through the window. I flung my arm over my eyes.”

—An excerpt from Barbara

How does your love of film influence the way you write?

As much as I do have a love of film, it’s a complicated love.

The book was my way of processing film as a modern technology. The film camera can be used as a tool for making art, but it is also a machine for making images.

The camera doesn’t truly need the human in order for it to make a picture. Humans build and control cameras, but once they’re going they could record with or without a person present. So the camera is, in a way, anti-human. and it has become our main conduit for ‘seeing’ real things we do not have physical access to.

Additionally, it makes images from reality, it captures the ‘real’ more perfectly than a painting or drawing. Because of film everyone can share a mental picture of what Marylin Monroe really looked like. Because of film we can all picture what a mushroom cloud from an atomic bomb looks like.

In one sense this has all been thoroughly explored by theorists and film scholars, but I think it’s so profoundly disturbing and consciousness changing that I still wanted to write about it. Film influences the way everyone thinks, it shapes the ways our minds form images and the way we experience the rhythm of life.

Writing belongs more in the realm of painting and drawing for me. I can create a string of words about a film or about an actress but it is never like or unlike film because words must be filtered through the human body both by the writer and the reader. So I guess I am writing with and against film as an object that is always far away.

There’s a wonderful section on your website called “The Barbara Files”—can you talk a bit about how film, photography and music influenced the writing of your novel, and could you curate a pairing of five films and five books (or songs) for readers who are wanting to linger a little longer in the world of Barbara?

I think Barbara is all about mediation. The narrator knows herself through films and photographs and music, and I as the author came to imagine and channel the time of the 1940s-1970s by absorbing the fictions as well as the news and documentary versions of that period of time. It’s media all the way down.

Hopefully this is not a glib answer to the question but it’s all about the experience of looking and listening and making and feeling with and through a mass media reality. Therefore, it's a challenge to talk about the influence of this or that individual work when I can only think about media as the sea in which we and the characters all swim in.

In terms of specific works that I am actively imitating or referencing, here’s a curated list:

Films:

Wanda (1970) Barbara Loden

McCabe and Mrs. Miller (1971) Robert Altman

Monsieur Klein (1976) Joseph Losey

The Tennant (1976) Roman Polanski

Opening Night (1977) John Cassavetes

Books:

Basic Black with Pearls Helen Weinzweig, NYRB, 2018

A World Destroyed: Hiroshima and its Legacies Martin J. Sherwin, Stanford University Press, 1973

Light Years James Salter, Vintage International, 1995

Picture Cycle, Masha Tupitsyn, Semiotext(e), 2019

The Book of Franza, Ingeborg Bachmann, Hydra Books, 1999

What are you searching for, reaching towards, when you write?

Intimacy. Mood. To quietly, but effectively, articulate sublimated logics of the American empire.

Joni Murphy is a writer from Las Cruces, New Mexico who lives in New York City. Her third novel, Barbara, is out now with Astra House & Book*hug in Canada.

To buy a copy of Barbara, consider supporting one of Joni’s favorite bookstores: Topos Bookstore, Bookworks, Women and Children First, Librairie Saint Henri, Flying Books, and Shelf Life Books.

Interview by Emma Leokadia Walkiewicz

I so admire authors like Joni who are able to render historical fiction well! It seems so challenging to me!