An interview with Christine Lai

Literary house-building and the bliss of a perfect writing moment with the author of Landscapes

Christine Lai’s mesmeric debut novel Landscapes is a portrait of artistry, ecological collapse, and the ouroboric nature of memory.

Penelope spends her days archiving an extensive art collection (“an archive of remains”) while attempting, alongside her partner Aidan, to preserve what they can of the place they have called home for so many years. Set in a distressingly prescient future, the once-grand Mornington Hall is scarred and crumbling against the weight of a world catastrophically affected by climate change—“A nature diary composed over the past decade would read like a catalogue of losses. There was a time when catastrophe seemed far away. We glided through the seasons … Then change became visible.”

Together, Penelope and Aidan “avert decay by daily care, by the physical work of cleaning and mending, saving the house one piece at a time and accommodating as many travellers as possible in the rooms that remain intact”, despite its impending demolition. Landscapes adroitly employs themes of art and memory to propel its reader towards the final days at Mornington, which will coincide with the return of Aidan’s estranged brother Julian, “the man who forced himself upon me in the unbearable summer heat” twenty-two years earlier.

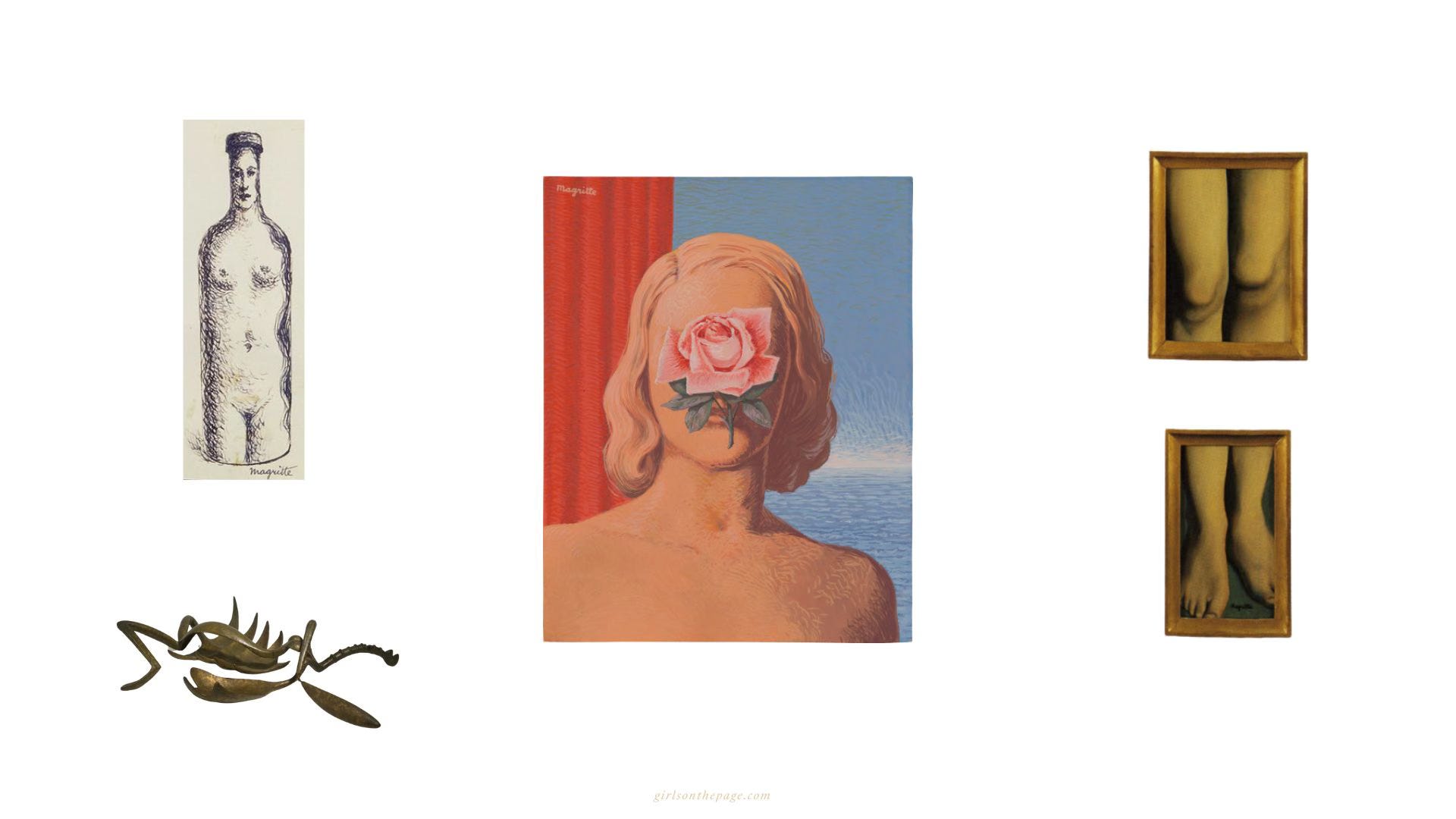

Written primarily in diary format, Penelope’s entries are interlaced with short essays on collected objects and pieces of art, including reflections on Edgar Degas’ Interieur, Giacometti, Picasso and Magritte’s Surrealist women (“frequently headless, and therefore sightless and voiceless”), and Ana Mendieta’s body of work ("My art comes out of rage and displacement. . . I think all art comes out of sublimated rage.”) The rage in Landscapes simmers, changes form; there is a lot—in the past and present—for Penelope to contend with. As the manor (and world) continues to disintegrate, and facing the imminent return of a man she has laboured to forget, Penelope vows “to go out there and look, again and again, as a way of paying tribute to all the life that has been lost.”

I want to begin with a quote from painter and sculptor Anselm Kiefer, which reminded me of Landscapes when I came across it:

“Ruins, for me, are the beginning. With the debris, you can construct new ideas. They are symbols of a beginning.”

Was there a central event or image that inspired the idea of Landscapes?

Thank you for that beautiful reference to Anselm Kiefer, whose work I’ve always loved. Landscapes began with the image of the ruin, of the dilapidated estate in which a woman sifts through the objects and artworks. During the writing process, I kept returning to a film still from Tacita Dean’s Bubble House (1999), which features the ruins of a house that was abandoned halfway through the construction process. The egg-shaped house was never completed, so it is vulnerable to the wind and rain of the Cayman’s “hurricane coast,” where the house is situated. This image challenges the idea of a stable shelter, and illustrates the ways in which humanmade structures are finite and fragile despite their seeming solidity. And much like how the human body is vulnerable to the outside world, the dilapidated house in Landscapes is porous to the environment.

But the ruin is also the site of fecundity and regeneration, of creative growth, as Kiefer points out. The semi-derelict house is a reminder that something has survived, that not all is rubble; in the midst of ruin, the protagonist Penelope rebuilds her life and writes her way through despair.

“As I feared, the work on this archive, the handling of these artifacts and images, means sliding slowly into memories.” —Penelope, from Landscapes

The sense of setting in Landscapes is so strong. As a writer, can you share how travel or being in a new place informs your writing? Do you find that writing and gathering inspiration is easier in a familiar setting or a brand-new one?

The novelty and thrill of an unfamiliar place trains the eye in a more rigorous way. New ideas and connections emerge when I’m walking down the streets of a distant city. But familiarity also compels me to see an old place anew, and allows for the repetition and re-seeing that is conducive to writing.

I’m currently reading The Traces, by Mairead Small Staid, an exquisite book that meditates on memory and travel, through the prism of Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities. Staid writes of how she “[spent] a single fall in Florence and will spend too many years to come attempting to reckon with those months.” Travel compresses and elongates time, so that even though it has been so long since I walked down the streets of Rome or Paris, those images find their way into the narrative. At some point, the boundary between the familiar and the unfamiliar fades.

Can you describe your experience writing Landscapes? Do you use file cards, plot extensively ahead of time, or were you able to take your time, and was the writing more serendipitous?

Writing materials are very important to me—I’m attached to specific notebooks and fountain pens. They take on an almost talismanic quality, and I write all my first drafts longhand. Everything goes in the notebook, which resembles a box or a repository of sentences, ideas, and images. Aside from notebooks, I also use index cards and post-its. Landscapes was not planned extensively before the writing. Rather, it developed organically, perhaps accidentally, through the research process that spanned several years. A particular painting might lead me to the backstory for a character; a historical fact might set an entire scene. The research provided what W. G. Sebald calls the “haphazardly assembled materials” that somehow accumulated gradually into a book. Contingency was key, and, indeed, serendipity.

What does an ideal writing day look like for you?

An ideal writing day always begins with reading, with being immersed in books. There is a shelf right by my desk that consists of the books which I return to again and again for nourishment, for guidance. Writing is never just about putting words on the page or on the screen. It is also about underlining, note-taking, reflecting, observing, being porous to the world. Sometimes I find it meaningful to just sit with a problem, to confront it somehow. I might also go for a long walk, watch films, or listen to music; I have been listening to Elgar’s Cello Concerto on repeat. And sometimes, a moment would arrive when all the readings, the notes, the artworks studied would be distilled into something in narrative form, and all the fragments would coalesce. That moment is a state of bliss unlike any other.

I loved what you wrote in the book’s acknowledgements, that the novel is “in some ways an archive of the texts that have been foundational to my thinking.”

I felt like the objects and artwork that Penelope references and is archiving throughout Landscapes encourages the reader to recalibrate and reconsider the scope of an experience, the scene, dialogue. Is there a piece of art that has done that for you lately?

Art is indispensable to me. In The Naïve and the Sentimental Novelist, Orhan Pamuk claims that writers are secretly envious of visual artists—I am certainly guilty of this. I’ve recently started doing research for an essay on the works of the Japanese American sculptor Ruth Asawa. In September, I saw an exhibition of her drawings and sculptures at the Whitney Museum in New York, and was so moved by her works. Asawa’s hanging wire sculptures are composed of shapes nesting within shapes, overlapping and flowing into one another. Her “continuous form within form” makes me think about the limitations of language and the ways in which the form of a text could also mimic the effect of these overlapping shapes. Despite their size, these sculptures seem light, levitating above the gallery floor as if free from gravitational pull. I have yet to think through Asawa’s works fully; they require attention and careful analysis, as they cannot be reduced to shallow biographical readings or neat categories. I will be spending time with the sculptures and drawings until I can truly see them.

“Remembering all this now, I am astounded by my own choices, by the absurdity of my younger self, with her desires and obsessions mired in reasons that have been eroded by time, leaving only the consequences, like scintillating shards of glass.” —Penelope

What have you learned through the writing and publishing of your first book? What is something you wish you knew, a piece of advice perhaps, that you would pass on to a writer working on their debut?

It has become commonplace to say that writing is arduous, though that is certainly true. It is also a revelatory experience, in that as I write, I learn something I did not know—whether that is a fact or a particular way of relating to the world or a previously unseen aspect of the self. In some ways, the insufficiency of knowledge drives me to write. Writing also provides the opportunity to engage with books that have influenced me; the novel is really an ongoing conversation with other texts, and the references or quotations are a way of paying homage.

Publishing opened my eyes as a reader, for I had very little knowledge of the mechanisms by which the books I love were produced. Some aspects of the industry have left me a bit disillusioned—the way marketing and publicity works, for example, which I wish I had known more about beforehand. But I have also forged important friendships, had innumerable enriching conversations, and found people in publishing who champion the project of literature.

This is perhaps ironic, but I am skeptical of writing advice in general, as every path is different. But I do think it’s important to read broadly, to read outside the English language, and to resist the market and its trends.

Which books (if any) served as mentors/inspiration to Landscapes? Or which books would you recommend to readers who enjoyed and are still submerged in the world of Landscapes?

Maria Gainza, Optic Nerve (trans. Thomas Bunstead)

Ayşegül Savaş, Walking on the Ceiling

Judith Schalansky, An Inventory of Losses (trans. Jackie Smith)

W. G. Sebald, Austerlitz (trans. Anthea Bell)

Kate Zambreno, Drifts

What is your relationship to the book now that it is in the hands of readers?

To know that readers have dedicated their time to the book, that it has moved them in some way—this makes everything worthwhile. And since reading is a private experience, the book is redefined by each individual reader; it is no longer strictly mine.

I once saw Landscapes as a kind of ending, for I did not think it would find a publisher. But now I see it as a beginning—hopefully the first in a series of books to which I can dedicate my life.

Christine Lai is the author of Landscapes, which has been highlighted on several “Most Anticipated” lists and selected as an Indie Next Pick by the American Booksellers Association. An earlier manuscript version was shortlisted for the 2020 Novel Prize, which rewards innovative novels that expand the possibilities of the form. Christine holds a PhD in English literature from University College London.

To buy a copy of Landscapes, consider supporting one of Christine’s favourite independent bookstores: The Paper Hound, Type Books, Librarie Drawn & Quarterly, The Center for Fiction, Community Bookstore, Two Dollar Radio HQ.