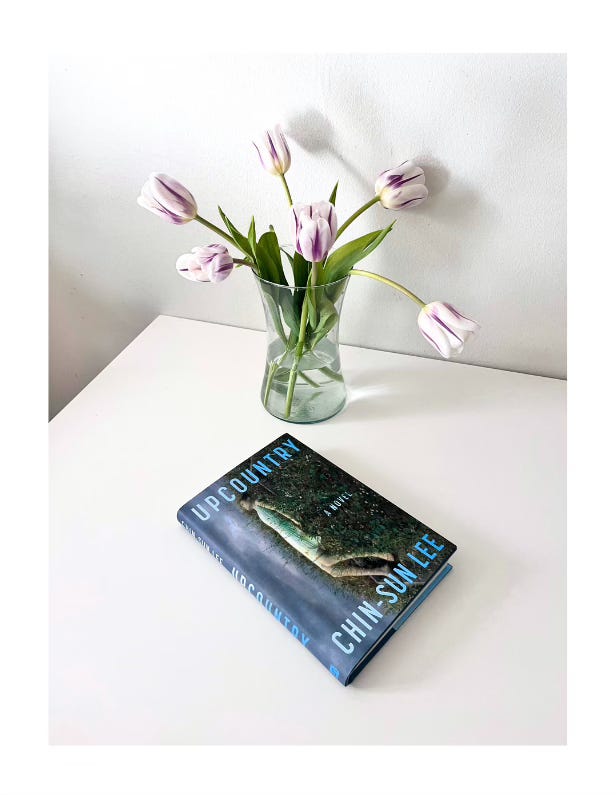

An interview with Chin-Sun Lee

The author of Upcountry discusses small town life, cults and the spirit houses hold

In her debut novel Upcountry, Chin-Sun Lee renders an intimate portrait of three women as they navigate tensions and tragedy in a small Catskills town. At the centre of it all, an old house—“a remodelled Greek Revival with blistered white clapboard walls and grey shutters missing several slats”, the fulcrum for Lee’s protagonists. There is Claire, a civil attorney from Hell’s Kitchen, who alongside her husband Sebastian, is eager to leave the city behind and turn the foreclosure property into their dream home. The house belonged to April, a childhood acquaintance of Claire’s and life-long resident of the area. A single mom, April was raising her three children in the house; her great-grandfather built it. For Anna, a member of a local religious group called The Eternals, “so young her pregnancy seemed almost obscene”, the house becomes a symbol of terror and loss.

As neighbours the protagonists reluctantly orbit one another, their struggles with finances, health, and relationships obvious as sun or rain—“the wildfire nature of small-town gossip”. The common threads of rural living pulse in the dark corners of an all-consuming house, a peculiar cult, and a town called Caliban. In time, and to varying degrees, the women also become recipients of one another’s anguish and grace. Lee does a beautiful job of illuminating the intimacy and tumult that lies beneath the surface of country life, telling the story of three women who are waging battles of the body, finances, and heart.

In Upcountry the protagonists, Claire, April and Anna, are intertwined in each other’s lives to a degree that really illustrates that whether you like it or not, when you live in a small community, people know your business! What was your experience living in a small town while writing this book?

During the summers of 2014 and 2015, I had the tremendous fortune of being able to live rent-free in a spare guesthouse owned by the parents of a good friend, near Durham, a small town in the Catskills. My friend’s mother was a stalwart member of the community and introduced me to everyone, so I quickly got immersed in all the local customs, activities, and yes, gossip! Everyone does know your business—but my experience was that, despite certain grievances or political and cultural differences, the majority of people got along. The close proximity of living in a small town practically dictates the need for civil behavior; otherwise, the social fabric completely unravels. Among other influences from that community, imagining such an unraveling in a compressed environment definitely inspired some of the events in my novel.

What was the initial image that inspired Upcountry? When did you know to follow that idea and flesh it out into a complete novel—what was the writing process like?

On one of my walks in the Catskills, I came across a slightly run-down house with a dilapidated, drained pool enclosed by a chain-link fence. It was an arresting sight because it had clearly not been in use for several years—weeds were growing out of cracks in the plaster (I would describe it almost verbatim as April’s house in the novel). For some reason, the image stuck with me, because it was such an obvious sign of financial downfall. The repercussions of the 2008 housing crisis were still evident in the rural towns I visited, and I’ve always been intrigued by the construct of class, so that house and those themes were the first seeds. Initially, I wrote the first chapter, “The Eternals,” as a standalone story, but then my friend Adam, who’s also a writer and my most trusted beta reader, suggested I could expand it into a novel. So, I have him to blame and thank! Attempting a novel was quite daunting and definitely involved trial and error. I’d only written stories up to that point, so at first, I thought the structure could be composed of interlinked stories with different POVs, like Elizabeth Strout’s wonderful Olive Kitteridge. But after writing three chapters in this vein, it felt too constraining and I thought, well, if I’m writing a novel, I might as well utilize the freedom to roam that that form allows. Then I quickly learned it can be very easy to spin out of control when your story has multiple characters, so at a certain point (usually around the 25K word mark) it’s helpful to step back, identify the main themes, and form a loose outline, even if it changes along the way. I also think it’s helpful to have an idea of the ending.

One of the main characters, Anna, was adopted as a child and raised in a religious group called The Eternals, who practice “an archaic form of Christianity rooted in Judaism”. There’s an air of mystery around them; the locals refer to them as a cult. I read in one of your previous interviews that The Eternals were based on a group you encountered in the Catskills while you were writing Upcountry. What makes cults—or any mysterious group—so interesting to read about?

What makes cults so interesting to me is the idea of voluntary compliance to a set of conscripted rules. It so goes against the grain of who I am, so it fascinates me. Objectively, I can see the appeal: you have an instant community, a sense of order, and a belief system that insulates you from the scary task of navigating this world alone. And as there are so many cults and religions, it’s clear that many people seek and need this guidance. I have no issue with it, as long as there’s no coercion or abuse of power involved. But I personally have no interest in ever joining one. Free will and independence are far too important to me.

The book is a poignant study of what draws a person to a place, and what keeps them there. We have Anna, whose adoptive parents gravitated to Caliban through their involvement with The Eternals, and Claire, who was allured by the bargain of the house in foreclosure, which once belonged to April, whose great-grandfather built the house and has lived in the area for her entire life. You crafted the world of this town and its characters with such realism and nuance—I’m curious whether there is a special place that you’re drawn to or enjoy returning to, which feeds you on an artistic or emotional level?

Thank you—I’m so glad the world of this novel resonated for you. A special place I love returning to is the small town in the Catskills that inspired Upcountry, not only because it sparked that creation but because those two summers were such a happy, productive time in my life. I’d just quit my fashion career and left New York City, where I’d lived for twenty years, to pursue writing full time. From 2014-2016, I was pretty transient, bopping from place to place, so having those two summers where I could just settle in was an enormous luxury. I just have such enormous fondness for my hosts and that community; every highway, farm, and creek. In my novel, everything turned dark and foreboding, but my lived reality was pure bliss. It’s funny, when I was younger, my special places were always beaches, and I still love them. But now I also really love being out in nature, in the woods and mountains. Smelling pine and hearing only twigs crackle under my feet as I walk along a trail makes me feel both calm and fully alert, connected to myself and the world around me.

“Claire looked away, and April shifted in her seat, taking another large sip of her drink. She wanted to finish it and get out of there. Something about Claire and being in the house, the way it was now . . . it gave her a cold, constricted, sad feeling, one she never experienced in all the years she lived there. For all its upgrades, the place creeped her out now, almost as if it were haunted; only rather than some unseen presence, what she felt was a palpable absence. Her place was small and messy and ugly. But there was life in it.”

—An excerpt from Upcountry

Taking place during the Great Recession, the house in Upcountry symbolizes something different for each character. For Claire it’s this unsurmountable project that never seems quite right or like it truly belongs to her, for April it’s a relic of a life that has slipped away, and to Anna it becomes a reminder of a horrific loss. I thought a lot about Gaston Bachelard’s Poetics of Space while reflecting on Upcountry—the home as a living, breathing part of oneself. Can you describe what “home” means to you, and whether that influenced the character of the house in your novel?

The home as a living, breathing part of its inhabitants is such an integral theme in gothic stories, and it’s one that very much influenced how I portrayed the house in my novel. I believe certain places are haunted; that a house or site can absorb and disgorge the energies of people who have suffered there or perpetrated atrocities—or conversely, been happy and at peace. “Home” to me is a place that feels welcoming, where I have community and feel comfortable, and where I’ve spent enough time to imprint my particular history—my scent, my habits, my belongings, how I occupy each room. It takes time to get acquainted with a house, to ease into its space and convert it into something that feels like your own.

Which three books will readers enjoy—whether similar in subject matter/tone, or books that inspired the writing of your novel—as a supplemental reading once they finish Upcountry?

Samantha Hunt’s atmospheric gothic novel, Mr. Splitfoot, takes place mostly in Upstate New York, and has elements of the occult and supernatural; Sara Lippman’s Lech has thematic overlaps—it’s set in the Catskills and involves real estate, a drowning, and a local religious group—though it’s tonally quite different, with a wonderful film of sleaze; and lastly, Ira Levin’s classic, Rosemary’s Baby, which I reread to convey the suspicious distrust my character Anna begins to harbor toward the cult’s matrons.

You had another career (in fashion!) before deciding to become a writer. What was that shift like, and what advice can you offer to someone who is working on their first novel?

It was not an easy shift, but I was frankly burned out from my design career and getting older, and after taking a few writing workshops and then getting my MFA, I felt I just had to give writing full-time a real shot. I applied to the Playa Artist Residency and when I got accepted in 2014, I decided to quit my job, leave NYC, and take a year off to write. After only one week at Playa, I knew I was never going back to fashion. That marked the beginning of my transient period, which led to my summers in the Catskills. I’ve taken those kinds of calculated risks in my life before, and they’ve always paid off. That said, I’m aware not everyone can do so. I had money saved and no dependents, so I was free and able to make that dramatic break. Every writer approaches their discipline differently, but a general advice I would give to first-time novelists is to write purely, for yourself, into your deepest obsessions. Don’t worry about marketability, especially in the first draft, because that’s so hard to predict anyway. And find your literary community—engage with other writers, because they will be your readers, critics, and support system. Lastly, learn to roll with the rejections. Publishing is a tough business, which we have very little control over. You constantly have to remind yourself why you’ve chosen this particular form of expression. In the end, it has to be about the compulsion to make art.

Chin-Sun Lee is the author of the debut novel Upcountry (Unnamed Press 2023), and a contributor to the New York Times bestselling anthology Women in Clothes (Blue Rider Press/Penguin 2014). Her work has also appeared in Electric Literature, Literary Hub, The Georgia Review, and Joyland, among other publications. She lives in New Orleans.

To buy a copy of Upcountry, consider supporting one of Chin-Sun’s favorite book stores: Octavia Books, Books Are Magic, Yu and Me Books, Skylight, and Powell’s.

I absolutely LOVE your interviews... And this interview was no exception! Such a great insight into the process of writing. Thoroughly enjoyed this!!